by Andrew Pace FCRH’22

The physical qualities of books, regardless of the content of the text itself, such as condition, format, design, fonts, and many more are valuable pointers to show how and by whom a book would have been used during its lifetime. Bibliographical records on the author and publisher can also help the reader understand the style in which the book was written and published. There is no better instance where this is the case than in Sefer Mitsvot ha-gadol by Moses ben Jacob of Coucy and published by the world-renowned Venetian publisher Daniel Bomberg in 1546/7.

Sefer Mitsvot ha-gadol is arguably Moses ben Jacob of Coucy’s most celebrated work. Fordham owns two copies of the 1546/7 edition. The Mitsvot ha-gadol, as it is commonly known, or “Se-Ma-G,” for short, includes the principles of the Rabbinic Oral Law and is divided into two sections: positive and negative precepts.[1] Due to its popularity and importance to rabbinic learning, the Mitsvot ha-gadol had been widely distributed in the Middle Ages and published in print several times as well.[2]

Its first publication took place in Rome sometime between 1469 and 1480, by Obadiah, Menasheh and Benjamin of Rome.[3] Subsequently, it was published in 1488 by Gershom Soncino in Soncino, the Duchy of Milan.[4] According to Israel Moses Ta-Shema, the final publication of this book during the pre-modern era took place in 1546 by Daniel Bomberg.[5] This edition was the last until the nineteenth century. Bomberg’s print shop in Venice, Italy, became famous for its Hebrew publications, including the first full edition of the Talmud, with what would be come a standard foliation of the work. There have also been a number of great scholars who have written commentaries on this work including, Isaac Stein, Joseph Colon, Elijah Mizrachi, Solomon Luria, and Hayyim Benveniste. However, as demonstrated by the lack of publications after 1546/7, the Mitsvot ha-gadol fell out of use, likely because it was replaced by the Shulhan Arukh around the time it was published in 1565.[6]

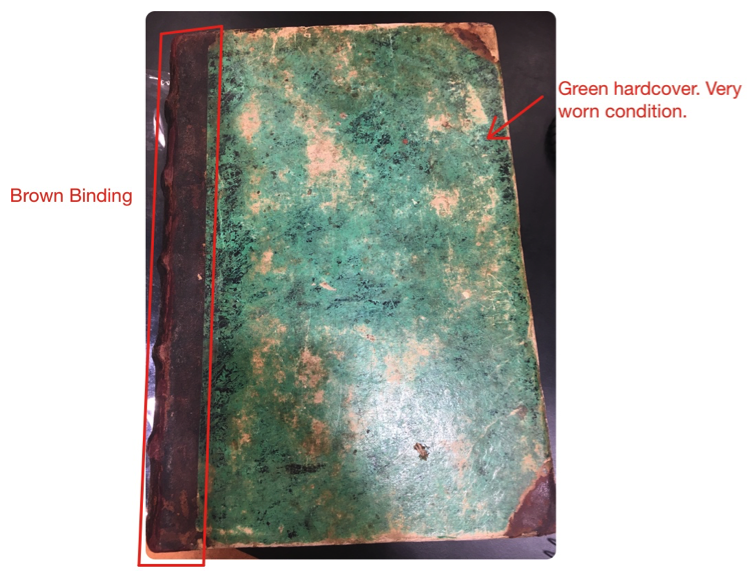

Fordham’s unexpurgated copy of Sefer Mitsvot ha-gadol is bound in a green cardboard cover with brown leather spine. The book measures thirty-two-point-five centimeters by twenty-three centimeters (Figure 1).

The large size of this book suggests that it was used as a reference book. The worn condition of the cover shows that it was frequently used.

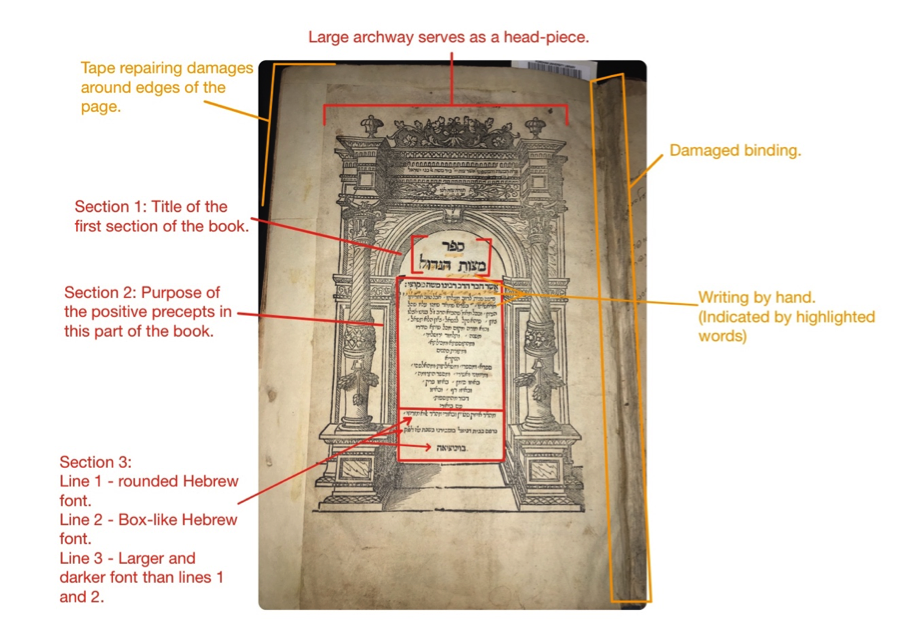

Although the outside of the book gives the reader a general understanding of its use, the pages tell a whole story in themselves. The title page of the Mitsvot ha-gadol has a large image of an archway with words embedded under the arch, known as a head-piece (Figure 2).[7]

These words are divided into three sections. The topmost set of words is arranged in two lines of dark black letters which are written in the largest font size out of the four sections. This is the title of the respective section of the book which follows this page. The second section of words is split into two identically-shaped paragraphs, preceded by a line of words with a larger text size than the two paragraphs, but smaller than the first section of words. These paragraphs taper down from a full line to one word at the bottom, resembling two upside-down triangles on top of each other. Moreover, the size of the text of this section is quite smaller than that of the first section and is printed in a different typeset. This text briefly explains the purpose and usefulness the positives precepts which are held in the first part of the book.[8] The third and final section of text presents itself in three lines which are separated by a space. The first line is very similar to the second, except that the first line is written in more of a rounded Hebrew font, while the font of the second line seems to be much more boxlike or square. However, the third line is much different than both. This line is very short and has a larger, broader font than lines one and two. These three lines are likely the closing remarks of the paragraphs in the second section of words.

While there is much to say about the text of the title page, the relatively poor physical condition of the page is immediately apparent as well (Fig. 2). There is tape all around the edges of the page indicating that there was damage which needed to be repaired. The binding is visibly very worn, weak and appears to have water damage. Finally, there is also writing which was done by hand in between the lines and letters of the above-mentioned three sections of words. Ironically enough, on the inside cover of the book and adjacent to the title page, someone had written, “Writing in this book is prohibited,” about fifteen times in Hebrew (Fig. 3).

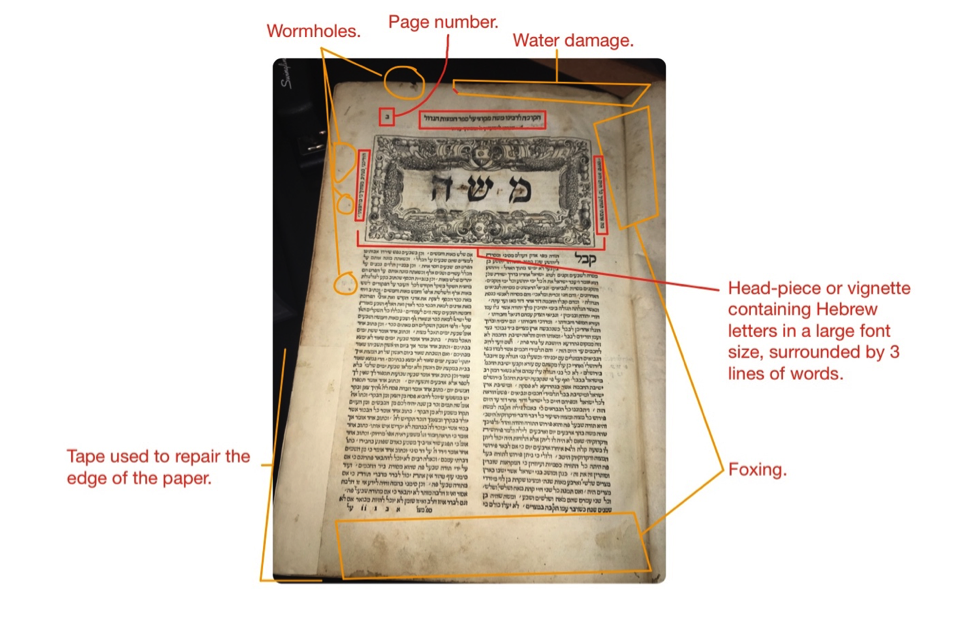

The age of this book is apparent on the page following the title page as well (Figure 4). All over the page are spots and browning that come with the book aging process. This process is known as “foxing.” Besides the foxing on this page, there are also holes in the paper which are seen on the majority of the pages, known as “wormholes.”[9]

As consistent with the title page, there is also water damage and tape on the edges of the paper. Besides the physical qualities of this page, there is also evidence of Daniel Bomberg’s employment of foliation in the top left corner above the text, which made it easier to navigate a large resource such as the Mitsvot ha-gadol.[10] Furthermore, this page has three large Hebrew letters at the top of the page boxed in by an ornate design, which is displayed in a similar fashion to a head-piece or vignette.[11] One may also note that at the top of the page and besides the ornate box there are large words which most likely identify the section of the book that the reader is currently in. Finally, where the text begins in the first paragraph, the first Hebrew word is capitalized. This typographical method is used to add emphasis and is known as an initial or drop cap.[12] While the first page holds many particular observations, the rest of the book is more or less quite uniformly designed.

The standard page in the Mitsvot ha-gadol includes two columns of text (Figure 5). Beside the columns and in indented sections of the paragraphs are notes in a smaller font size than the text. These serve as references to the sources in which Moses ben Jacob used. Many of these, but not all, are direct references to the Sephardic Jewish philosopher Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah, which is said to be directly cited on at least every page.[13] These pages are numbered in the top outer corners and have large words at the top of the page which identify the section of the book as either the positive or negative precepts.[14] Additionally, at the end of the first section, there are large darkened words which specify that the section is over, and a new section begins with the same archway that is observed on the title page of the book (Figure 6).

The Sefer Mitsvot ha-gadol was written by Moses ben Jacob of Coucy, who was born in France and, in 1236, became an itinerant preacher in Spain.[15] During the rise of rationalization in Spain, the adherence to the precepts of the Jewish faith became fairly permissive. Consequently, Moses ben Jacob began his work on the Mitsvot ha-gadol to address the precepts and commandments. He arranged, as is traditional, the precepts into positive and negative sections of the book and organized them in such a way that the reader could distinguish which applied to their time and which did not.[16] Although educating its reader on the precepts may have been a primary motivating factor behind the writing of the Mitsvot ha-gadol, Moses ben Jacob also states in the introduction of the positive precepts that, “A man may learn his entire life and still fail to attain knowledge of a particular commandment, and this is due to the length of the Talmud, the dialectic reasoning, and to the fact that one commandment may appear in several places.”[17] So, this book was also meant to be used alongside the Talmud as a reference due to its complexity, and, therefore, the target audience would have been narrowed to scholars who were already immersed in Talmudic studies. Following the great success of the Sefer Mitsvot ha-gadol, Moses ben Jacob also went on to author another work. He wrote a commentary on the tractate Yoma which was titled “Tosefot Yeshanim.” This commentary, however, was not published until 1735 in Berlin.[18]

Daniel Bomberg, the printer of Fordham’s Sefer Mitsvot ha-gadol, was one of the most prolific publishers of Jewish texts during the 16th century. Bomberg, a native of Antwerp, moved to Venice in 1516, which was the center of Jewish and Christian writing in the 15th century.[19] Here, he opened a print shop and began specializing in printing Hebrew bibles, famously printing the Rabbinic Bible, which became known as the Bomberg Bible in 1517. The Bomberg Bible solidified Daniel Bomberg’s reputation amongst 16th-century printers because, through its many successive printings, it became the golden standard for Hebrew scriptures in the Jewish tradition.[20] In dominating the competitive printing scene, Bomberg also took business from other printers, such as Gershom Soncino, the preeminent printer of medieval Hebrew works and one of the earlier publishers of the Sefer Mitsvot ha-gadol (in 1488). Years later, Soncino wrote, “The Venetian printers copied my books and published, in addition, whatever they could lay their hands on. They tried hard to ruin me…”[21] Clearly referring to Bomberg as a “Venetian printer,” Soncino admits that Bomberg was outpacing him and, subsequently, ruining his career. The very notion that Bomberg could take a work, such as the Mitsvot ha-gadol, from the distinguished Gershom Soncino and print a superior version in his own style is a testament to his success.

Daniel Bomberg also published dozens of other influential pieces of Hebrew literature. This included works like Sefer ha-shorashim by David Kimhi and Elijah Levita, which goes into detail about the Hebrew language itself, and Hamishah humshe Torah ; Neviim Rishonim; Arba `a Neviim Aharonim ; Ketuvim,” a collection of commentaries on the Old Testament of the Bible compiled from four volumes into one book in 1521.[22] Bomberg also famously printed the first full foliated edition of the Talmud in 1520. A specialty of his, the addition of page numbers made reading texts like the Talmud much more accessible because it allowed people to easily locate sections of the book without having to refer to the chapter and verse. This foliation became standardized in the printing of the Talmud.[23]

The Sefer Mitsvot ha-gadol has engraved its name as one of the most distinguished pieces of Hebrew works in medieval Europe. It presented the negative and positive precepts in a clear and usable way. When the printing press was invented, it was one of the first Hebrew works to be printed, and the book had such success that several distinguished scholars wrote commentaries on the work. Fordham’s copy of the Mitsvot ha-gadol was printed in 1546/7, by the notable printer, Daniel Bomberg, in Venice. This was the last publication of this important halakhic compendium in the pre-modern period and was not republished again until the 19th century. The fact that it survived throughout the centuries and was still studied by scholars in Europe even after it ceased to be published points towards its importance. Furthermore, as evidenced by the physical examination of this book, it was undeniably frequently used, its owners trying to repair and preserve the work. Although it was not published again until the 1800s, it is beyond doubt that the Sefer Mitsvot ha-gadol has left a lasting impact on the history of Jewish law and culture.

This essay was written in fall of 2018, during Andrew Pace’s first semester at Fordham, within a course on modern Jewish history (HIST 1851) taught by Professor Magda Teter. Their essays, some of which will be featured here, were published in a volume “You Can Judge Books by Their Covers Jewish History through Used Books.” Fordham’s Judaica collection prides itself in collecting books that were used and popular, often quite quotidian and ordinary, for they reflect a broader Jewish culture that might not be visible through expensive extraordinary items.

[1] Israel Moses Ta-Shema, “Moses Ben Jacob of Coucy,” Encyclopaedia Judaica 14 (2018).

[2] Ta-Shema, “Moses Ben Jacob of Coucy.”

[3] of Coucy Moses ben Jacob, Sefer Mitsvot Gadol. (Rome: [Rome] : [Obadiah, Menasheh and Benjamin of Rome, ca. 1469-1472], 1469-1480).

[4] of Coucy Moses ben Jacob, Sefer Mizot Gadol (Book of Precepts). (Duchy of Milan Gershom Soncino, 1488).

[5] Ta-Shema, “Moses Ben Jacob of Coucy.”

[6] Conversation with Professor Teter; September 26, 2018

[7] John Carter and Nicolas Barker, Abc for Book Collectors, 8th ed. (New Castle, DE; London: Oak Knoll Press; The British Library, 2004).

[8] Yehuda Dov Galinsky, “The Significance of Form: R. Moses of Coucy’s Reading Audience and His ‘Sefer Ha-Miẓvot’,” AJS Review, no. 2 (2011).

[9] Dialogue with Professor Teter; September 26, 2018

[10] Professor Magda Teter Class Lecture; September 6, 2018

[11] Carter and Barker, Abc for Book Collectors.

[12] Ina Saltz, Typography Essentials : 100 Design Principles for Working with Type, Design Essentials (Quayside Publishing Group, 2009).

[13] Ta-Shema, “Moses Ben Jacob of Coucy.”

[14] Ta-Shema, “Moses Ben Jacob of Coucy.”

[15] Ta-Shema, “Moses Ben Jacob of Coucy.”

[16] Galinsky, “The Significance of Form.”

[17] Galinsky, “The Significance of Form.”

[18] of Coucy Moses ben Jacob, Tosefot Yeshanim. (Berlin1735).

[19] “Bomberg, Daniel (1483–1553) [Bomberg, Daniel],” The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance.

[20] David Shepherd, “Before Bomberg: The Case of the Targum of Job in the Rabbinic Bible and the Solger Codex (Ms Nürnberg),” Biblica 79, no. 3 (1998).

[21] Jacob Rader Marcus, 1896-1995. and Marc. Saperstein, The Jew in the Medieval World: A Source Book, 315-1791, Rev. ed. ed. (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1999).

[22] Daniel Bomberg, Hamishah Humshe Torah ; Neviim Rishonim ; Arba`a Neviim Aharonim ; [Ketuvim]. Nidpas shenit ed. (Venice, Italy: Daniel Bomberg, 1521); David Kimhi and Elijah Levita, Sefer Ha-Shorashim. (Daniel Bomberg, 1546).

[23] Professor Magda Teter Class Lecture; September 6, 2018