Liliya Fisher FCRH’21

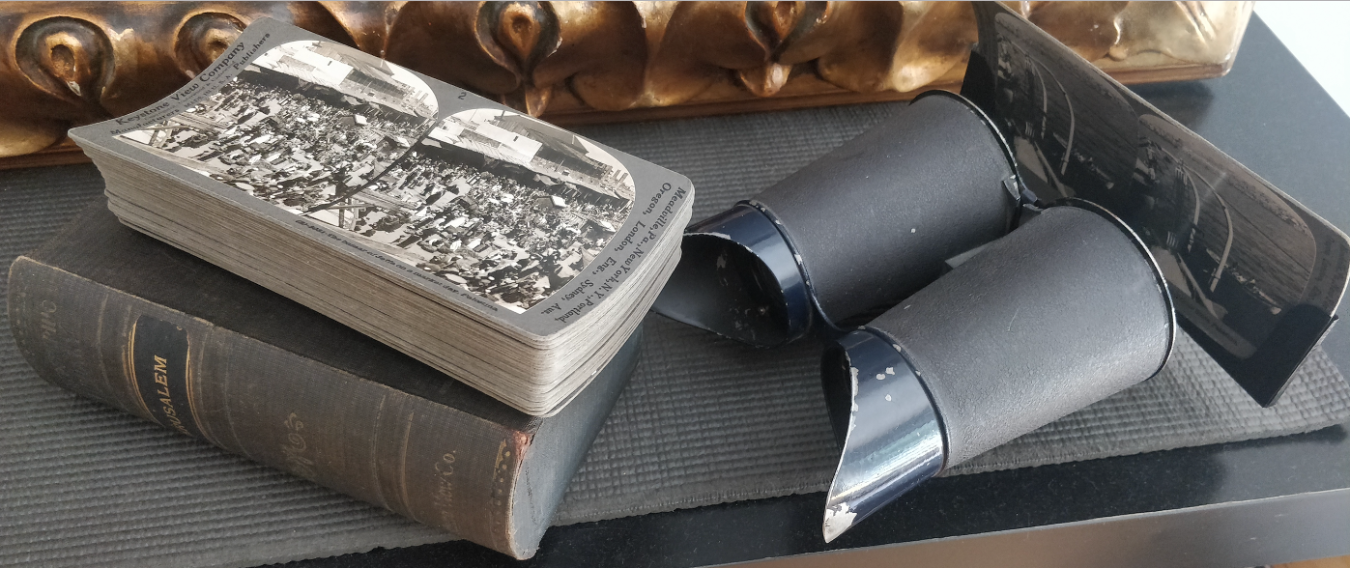

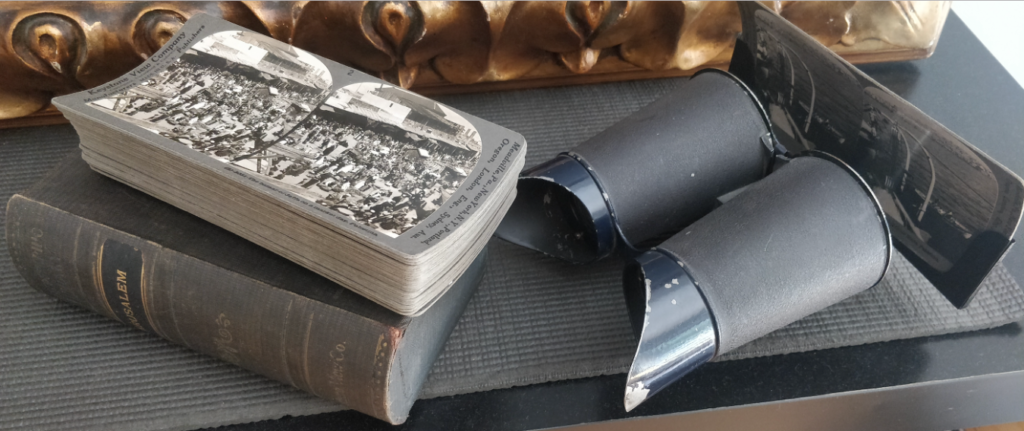

This piece is a stereographic set of 30 images taken on a trip to the Holy Land in 1896. The images were taken by Bert and Elmer Underwood. The photos were published by Underwood & Underwood, a well-known stereoscopic company, owned by Bert and Elmer Underwood. The 30 images in this set are part of a larger collection from the Underwoods’ trip that consists of a total of 100 images of the journey to and at the Holy Land.

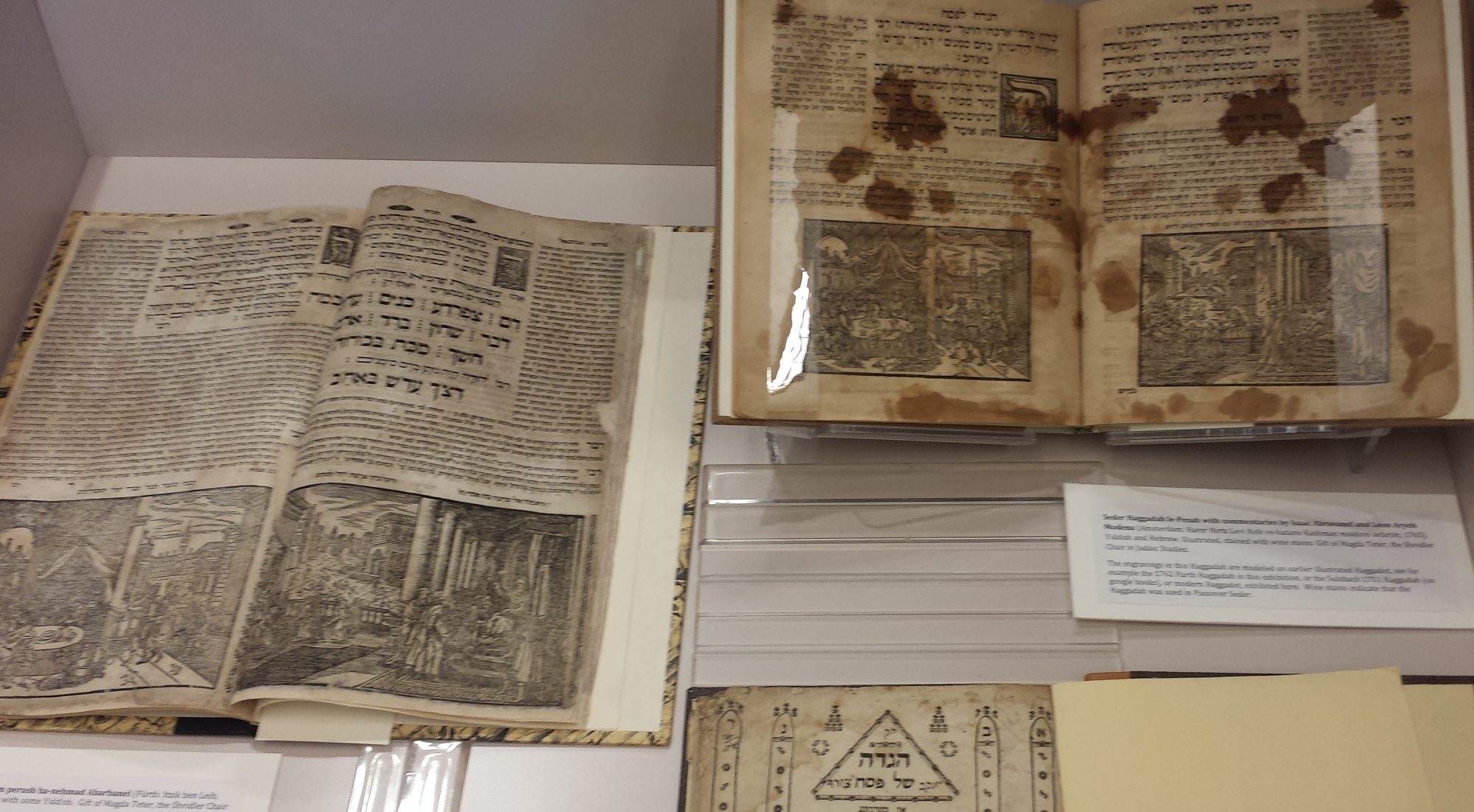

In 1900, a 220-page book, titled Traveling in the Holy Land Through Stereoscope; a personally conducted tour by Jesse Lyman Hurlbut, D.D., written by Reverend Jesse Lyman Hurlbut, D.D., was published to accompany the photos. Jesse Lyman Hurlbut, D.D. was a clergyman of the American Episcopal Church and held positions all over New Jersey.[i] The book contains corresponding texts to each of the 100 photographs as well as maps pinpointing the sites that guide the viewer through the images. The current exhibit only contains 30 photographs and not the book.

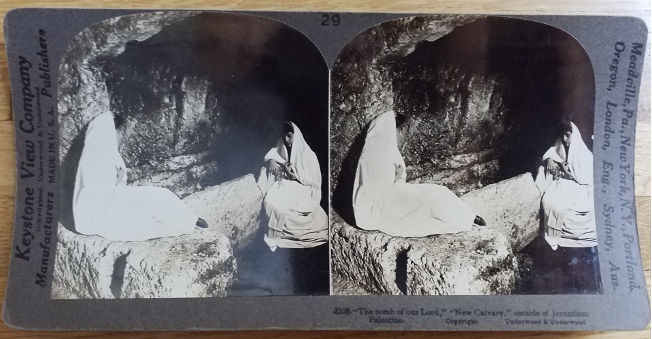

The 30 photographs in this series begin in the Port of Jaffa. This port is a common entryway to the Holy Land for pilgrims, so it is fitting that the photo series begins there. The photo of the camel caravan is used symbolically to show the pilgrims making their way out of Jaffa, further inland. The Underwoods photographed the plains of Sharon, passing through Lydda, Mizpah, and Mount Scopus. These sites are historical and can be traced to biblical narratives. As the Underwoods approached Jerusalem, they photographed the Damascus Gate, with a great view of the city and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Jaffa Gate, and the ancient walls. Other photos specific to Jerusalem include the Valley of Kedron, Tombs of the Prophets, the Garden of Gethsemane, Mount of Olives, and other panoramic scenes. The Underwoods also photographed lepers, pilgrims, the Dome of the Rock, the Rock itself, the Wailing Wall, David Street, and Christian Street. They even staged two Syrian women for photographs at the tomb of Jesus, to reenact the finding of the risen Jesus.

This set of photographs is diverse in a number of ways. This diversity can be seen through the different subjects that the Underwoods chose to photograph. In some photos, there are no people, such as the photo taken outside the Dome of the Rock. In others, the streets and the frame are completely full of people, such as the photo of the Greek Easter procession of the Patriarchs. The final photo in this specific exhibit shows the pass of Upper Beth-Horon, which is an ancient city northeast of Jerusalem. The photos also capture the diversity of people who live in and visit the city. There is no doubt that these photos encapsulated the various types of people in the city, including Greeks, Ottomans, and Jews.

Stereoscopic photography is a form of photography that was popular between 1870 and 1920. To view these photos properly, you need a stereoscope, a device that looks similar to binoculars. The card mount photo card has two images placed next to each other. When the viewer looks through the stereoscope, the images appear 3-D. This device was fascinating to users in this time period, as it was the first of its kind, and the art of photography was quickly evolving.[ii] The hope, expressed by Hurlbut, was to create an experience beyond what a 2- dimensional picture provides. The use of a stereoscope thus creates a super realistic depiction of its scenes. Adding these depths and dimensions creates grander photographs that are beyond the simple, 2-dimensional photographs. This also aids in the purpose of the photographs, allowing those who could not visit Jerusalem in person to experience the Holy Land from their homes and elsewhere. Pairing the images with descriptions, which are written in English, Underwood, Underwood and Hurlburt created an all-inclusive experience. With Hurlburt’s accompanying book, the addition of maps that traces the path of pilgrimage also creates inclusivity and immersion in the Holy Land experience. These maps can be accessed in the back of Hurlbut’s book.

To the Underwood brothers, photography was powerful, especially in religious contexts. According to Rachel McBride Lindsey in A Communion of Shadows, the power of photography “facilitate[s] access to the sacred site without physical travel.”[iii] The photographs, especially when viewed in 3D through a stereoscope, transport the viewer to the Holy Land. The 3-dimensional image is an involved experience. Lindsey quotes a viewer, for example, who reported that the experience of viewing these photographs “is almost the same as if we were actually traveling in the Holy Land.”[iv] In Hurlbut’s introduction, he states that the photos make “the Bible real to us.”[v] Since the Bible does not contain photographs, these early photographs were important because they allowed viewers to visualize the places about which they read in their Bibles or heard in their church services. Because most people could not make the journey due to financial or other reasons, these photographs transported them to the Holy Land while they remained, physically, at home in the United States or elsewhere. The photos thus served as many people’s first images of the real Levant and Holy Land, making once ancient lands a little more accessible. Importantly, these images represented biblical Jerusalem, not contemporaryJerusalem. They thus transported the viewer not only through space but also through time, and specifically to the time of Jesus. This is a different type of immersive experience, more than simply reading biblical texts. As a minister, the words of Hurlbut were highly valued in his religious community and to religious users of this stereoscope series. His support of stereoscopic photographs helped make them popular and relevant in religious educational settings.

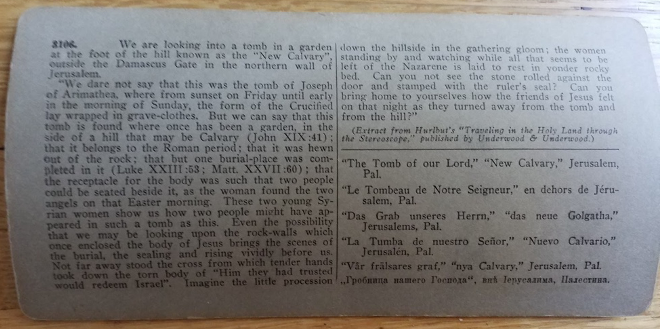

One important image to highlight is this context is the “Tomb of Our Lord.” According to Lindsey and the accompanying description on the card mount, the two women in the image were Syrian girls that Bert and Elmer staged for the photograph. This staging is based on Biblical Protestant interpretation. Hurlbut references three different versions of the same description of the tomb. First, he mentions John 19:41, “Now in the place where He was crucified there was a garden, and in the garden a new tomb in which no one had yet been laid.” He also refers to Luke 23:53, “Then he took it down, wrapped it in linen, and laid it in a tomb that was hewn out of the rock, where no one had ever lain before,” and Matthew 27:60, “and laid it in his new tomb which he had hewn out of the rock; and he rolled a large stone against the door of the tomb, and departed.” Hurlbut exclaims in the card’s description: “Even the possibility that we may be looking upon the rock walls which once enclosed the body of Jesus brings the scenes of the burial, the sealing and rising vividly before us.”[vi]

This stereoscope series was not unique: it was part of a broader photographic trend. As stereoscope photography was the new craze in the mid 1800s, it made its way into the religious realm. Popular religious sets include Holy Land Tours (1900) and The Life of Christ (1904).[vii] Usually, when images of the Middle East, Levant, and holy sites therein were published, many were published as tourism or archeological photographs, not religious photographs.[viii] To adapt them for religious purposes, they would be published as “scriptural interpretation.”[ix] This framing as “interpretation” was important because the photographers and authors did not want them to be misunderstood as icons or sacrilegious images. Moreover, the photographs and book were sold through the Bible Study Department of the publishing company.

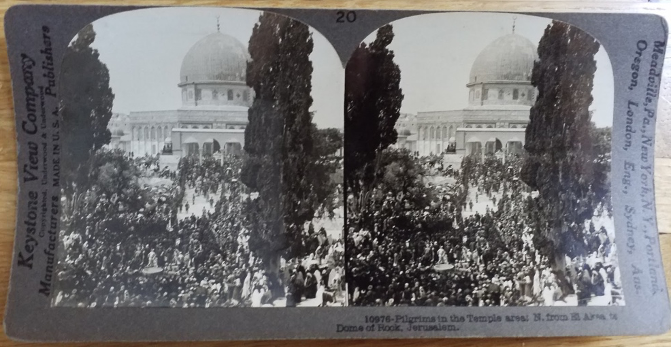

These images did not only serve as a form of travel from home. They also served a pedagogical purpose as religious educational materials. Some ministers actively supported the use of these stereographs as learning tools. The stereoscope images of the Holy Land, for example, became teaching tools in Sunday school programs and home schooling for American Protestants.[x] The cryptic description of the image, “Pilgrims in the Temple are: N. from El Aksa to Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem,” shown above, is a great example of this. The description on the back of this card is an excerpt from Hurlbut’s book. He first gives a general, geographical description: “We are standing in front of the Mosque El Aksa, just south of the Temple area, looking north to the Dome of the Rock.”[xi] After Hurlbut establishes the location of the image, he acknowledges that the people seen in the photo are “Mohammedans,” and then he quickly shifts to describe the photograph’s biblical significance. This gloss of a non-Christian pilgrim comes off as disrespectful, but Hurlbut seems mainly to be considering his Protestant audience, rather than Jerusalem’s local population. Rather than dwelling on the mosque itself, Hurlbut explains how this is the site of Solomon’s newly built temple. Then he jumps to explain how King Hezekiah held congregations in this same location. Hurlbut continues to take his reader through the history of the site, with reference to Jesus at the Feast of Tabernacles, stating that “That voice sounded out over this very area and before such a throng as this.”[xii] It is not necessarily important to question how historically accurate Hurlbut is in his geography skills. More important, for our purposes here, is to recognize that he sought to provide context for his congregation or whomever else was reading his descriptions. The fact that Solomon, Jesus, and other famous religious figures were in the general vicinity of the site is proof enough for Hurlbut to keep the faith strong.

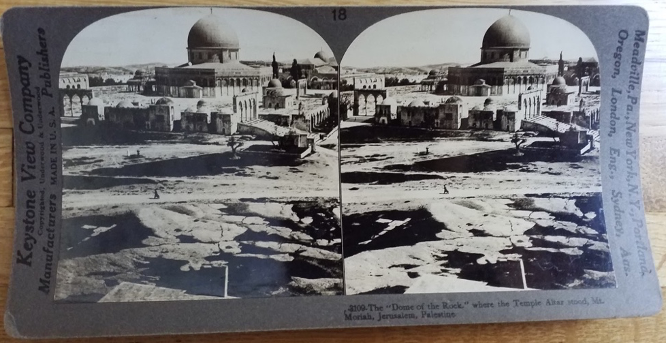

The written descriptions of the images that appear on the back of the photographs play a key explanatory role. Without these explanations that come with the images, viewers would have a difficult time understanding some of the subjects of the images. A worry in general with photography is that the framing of the image is decided by the photographer. One must ponder not only what is included in the image, but also what is excluded. The viewer must be wary of any hints of a forced interpretation of the image. Consider, for example, image 18 of the Dome of the Rock, as seen in Figure 5. The angle chosen provides a lot of foreground in the image. Why did the Underwood brothers choose this angle? It frames the Dome of the Rock nicely, but the disproportionate focus on the foreground is, at first glance, baffling. The description explains, however, that this image was taken at the northwest corner of the Haram enclosure, and that the foreground shows the “native rock of Mount Moriah, just as Abraham found it when he climbed this hill for the offering up of his son.”[xiii] We learn from this description that the focus of the photo is not the Dome of the Rock, as one might expect, but rather the ground before it, which is connected to Abrahamic history.

These stereoscopic images are a fascinating addition to the Fordham collection. While the collection holds only 30 of the 100 images, they tell a great deal about Jerusalem in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s as well as the relationship that American Protestants sought to cultivate with Jerusalem from afar. The images contextualize modern pilgrimages and visits to the Holy Land with the new technology of the stereoscope. Bert and Elmer Underwood worked to reimagine the world of photography. These 3-dimensional images not only brought a new form of entertainment, but also changed how a biblical scene could be portrayed and viewed. The role of stereoscopic photographs in religious devotion and education is likewise important as the photographs bring those who cannot make pilgrimage closer to the sites through the medium of photography. Through such series, photography became an acceptable educational resource used to teach biblical narratives to children and adults.

Liliya Fisher is a FCRH senior Psychology major and Bioethics minor from Albany, NY. She is a hiker, animal lover, and proud vegetarian who is currently on her way to join the Catskill 3500 Club with her dog, Patch.

This blog post was originally written for Prof. Sarit Kattan Gribetz’s “Medieval Jerusalem: Jewish Christian, Muslim Perspectives” course; the photographs and this essay will be featured in an upcoming exhibition at Fordham’s Walsh Library.

Bibliography:

Hurlbut , Jesse Lyman. “Introduction,” in Traveling in the Holy Land, through the Stereoscope: A Tour Personally Conducted by Jesse Lyman Hurlbut (Underwood and Underwood, 1900), pp. 10–14, archive.org/details/travelinginholyl00hurl/page/10/mode/2up.

Lindsey, Rachel McBride. A Communion of Shadows: Religion and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Smith-Pistelli, Della Dale. Reverend Jesse Lyman Hurlbut. 24 May 2018, www.geni.com/people/Reverend-Jesse-Hurlbut/6000000018605674334.

“Stereographs.” Retrieved December 07, 2020, from https://www.americanantiquarian.org/stereographs.htm

“Stereograph Cards – Background and Scope.” Background and Scope – Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (Library of Congress), Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/stereo/background.html.

[i] Smith-Pistelli, “Reverend Jesse Lyman Hurlbut.”

[ii] American Antiquarian Society, “Stereographs”; Library of Congress, “Stereograph Cards.”

[iii] Lindsey, A Communion of Shadows, 201.

[iv] Lindsey, A Communion of Shadows, 203.

[v] Hurlbut, Traveling in the Holy Land, 12.

[vi] Excerpt from image 3106; extract from Hurlbut, “Traveling in the Holy Land through the Stereoscope.”

[vii] Lindsey, A Communion of Shadows, 206.

[viii] Lindsey, A Communion of Shadows, 206.

[ix] Lindsey, A Communion of Shadows, 206.

[x] Lindsey, A Communion of Shadows, 210.

[xi] Back of card #10976, “Pilgrims in the Old Temple Courts.”

[xii] Back of card #10976, “Pilgrims in the Old Temple Courts.”

[xiii] Card #3109 image description, the “Dome of the Rock” where the Temple Altar stood, Mt. Moriah, Jerusalem, Palestine.”