By Julia Kohut

Mary Angeline Hallock published The Child’s History of the Fall of Jerusalem in 1869 in New York City through the American Tract Society. The book was part of a series that consisted of at least two other books, titled The Child’s History of King Solomon (1869) and The Child’s History of Daniel (1870). The book is a children’s chapter book. It contains large font and several illustrations throughout.

The cover of the book is a deep red and embossed with a leaf design. The words on the cover are written in gold. The two halves of the title, “The Child’s History of” and “the Fall of Jerusalem,” are written in two different fonts. An image of a Judea Capta coin, a coin Emperor Vespasian issued to commemorate the Roman victory in Jerusalem in 70 C.E., appears between the two parts of the title. The cover page has the same Judea Capta image, with the words “Vespasian’s Triumphal Midal” written underneath it. Fordham’s copy of the book appears to be in excellent condition. The front cover is slightly worn, and the color has somewhat faded, but that is expected for such an old book.

Not much is known about the author, Mary Angeline Hallock. She was, however, a prolific author who published multiple books with the American Tract Society. In addition to The Child’s History Series, the cover page of The Fall of Jerusalem also credits her with two other books, That Sweet Story of Old and Life of Paul. She published other books as well, including Bethlehem and Her Children (1859), Beasts and Birds of America, Europe, Asia and Africa (1870), and Story of Moses, or Desert Wanderings from Egypt to Canaan (1888). Her work with the American Tract Society, an evangelical publication, is most likely indicative of her religious upbringing and communal affiliation.[1] According to documents from the American Tract Society’s online archive, the group was created in 1825 for three main reasons. First, the Second Great Awakening in 1790 caused the widespread creation of new Christian groups and societies in America. Secondly, America was annexing states in great succession, and these Christian groups wanted a way to spread their faith to those living in these new territories. Lastly, there was a surge of immigration to America in the early 1800s, and so they felt the pressing need to educate the growing country and its new residents about their religion and its history, especially Jesus Christ.[2]

Based on this information, it is possible to assume that the American Tract Society published Christian authors who fit their narrative and bolstered their agenda. In addition, we know that Mary Angeline Lathrop married William Allen Hallock, the son of Reverend Moses Hallock, who worked for the American Tract Society and was fundamental to its success. Several of Mary Angeline Hallock’s books were already published with the American Tract Society when they wed. The couple was married before The Fall of Jerusalem was published.[3]

The Child’s History of the Fall of Jerusalem can be classified as historical fiction. While the historical information is accurate to a degree (determined through comparison to historical documents and Josephus’s works), the facts are told through a fictional father, Mr. Sherman, who converses with his teenaged son and daughter, Charlie and Jennie. The book is easy to understand and was probably intended for slightly older children. The main characters are 12 and 14, probably the imaged age of the book’s ideal readers. Throughout the book, Mr. Sherman assigns Charlie and Jennie their own research on people and events during Jerusalem’s destruction.[4] Hallock might have decided to frame the story in this way to inspire her young Christian audience to conduct their own research and further develop their knowledge about their faith while cultivating good study or educational habits.

Hallock provides background information on the city, beginning with Abraham taking Isaac to the land of Moriah. She explains that the Israelites took control of the city and that David became the king of Israel. She also briefly describes the Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes. Four of the ten chapters are devoted to significant people, including Josephus, Antonius Felix, Agrippa, and Titus.[5] Only three chapters are devoted specifically to the destruction. The last three chapters of the book examine three different themes of the destruction: hunger, famine, and death.

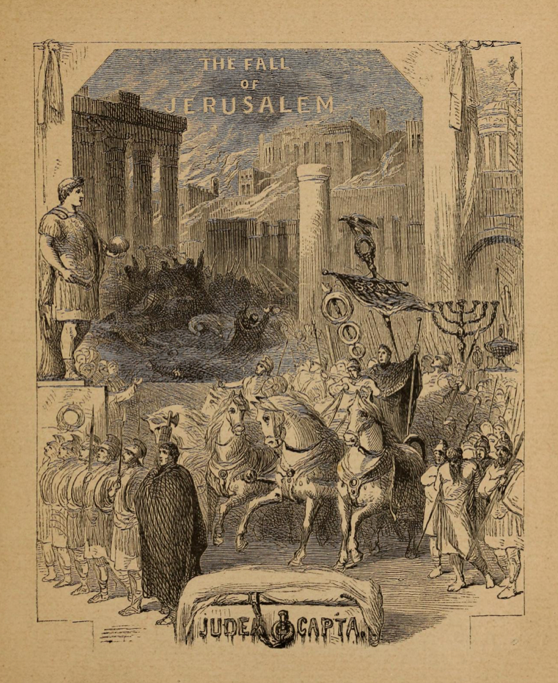

There are 21 illustrations throughout the book. Each of the ten chapters begins with an image depicting the main person or event introduced in that section. The illustrations are incredibly detailed drawings and usually depict a Roman perspective. Roman soldiers are often in the forefront of the image and are drawn in more detail than Jewish aspects or people. Furthermore, several of the illustrations include “SPQR” in their borders. SPQR stands for the Senate and People of Rome (Senatus Populusque Romanus in Latin).

The first drawing (Figure 3, above) appears before the text begins. It depicts Roman control of the city with Roman soldiers standing in line. Juxtaposed to the Roman soldiers are disordered Jews on their knees in the background. Spears are pointed to a menorah, and the words “Judea Capta” are written at the bottom of the image alongside a Roman emblem. The second illustration (Figure 4, below), placed above the book’s opening lines, is a circular image of people walking into the city, some on horseback.

In this illustration (Figure 4), the people depicted on horses are most likely Roman Soldiers overseeing this movement of people. On one side of the circle is a crate with a jug, perhaps containing olive oil. On the other side is a table with a menorah and several ambiguous blocks. The circle is encased with a variation of Psalm 48:12: “Walk about Zion, and go round about her: tell the towers thereof. Mark ye well her bulwarks, consider her palaces; that ye may tell it to the generation following.” This psalm personifies Jerusalem as a woman and encourages pilgrimage to the city to spread its history to others. Both of these concepts are key themes in the Hebrew Bible and New Testament, and the citation of this Psalm alludes to this larger constellation of traditions, including to the feminization of Jerusalem in contexts of conquest in particular. Other illustrations in the book show Roman soldiers on horseback as well (see Figure 5 below).

The work’s final illustration (Figure 6) is found at the conclusion of the book where the story transitions from Jerusalem to Rome, with the erection of Vespasian’s Temple to Peace. The illustration depicts the iconic panel from the Arch of Titus, featuring what appears to be smiling Roman soldiers carrying the precious Jewish artifacts that were seized during the destruction to Rome (the relief on the Arch of Titus has also been interpreted by scholars to depict enslaved Jews carrying the temple objects).[6] The artifacts include a golden menorah and the Book of the Jewish Law set on a golden table.[7]

The Child’s History of the Fall of Jerusalem describes the city in a tone similar to biblical texts. The text emphasizes the inherent holiness and divinity of the city at various points throughout the narrative. For example, on page eight, Hallock writes: “Troy was no more than any other city, while Jerusalem is identified with the church of God in all ages.”[9] Like Jerusalem, the ancient city of Troy was a critical city. After a long and strenuous battle, Troy was conquered by the Greeks. Introducing Jerusalem as an important city to Christianity was a key strategy for Hallock, and probably the American Tract Society as well. This would have cemented the younger generation’s notion that Christianity and Jerusalem were intrinsically connected and that each played a part in the other’s history – and, in turn, in their own history and identity.

There is also an act of “othering” in the text that creates a divide between Christians and Jews, making the text slightly prejudicial and biased. For instance, in reference to the Jews, Mr. Sherman tells his children that “their sin lay in not believing. Their scriptures were very plain; and in perfect harmony with them were Christ’s life and miracles, which were sufficient proof of his divinity.”[10] Mr. Sherman tells his children that the Jews in ancient Jerusalem were negatively impacted because they did not accept Jesus Christ as their savior. The children who would have read this book are thus taught the same supersessionist lesson as Charlie and Jennie learn in the narrative. Potentially, an entire generation of young Christians in America grew up believing in their superiority over Jews and that their claim to Jerusalem was more robust than anyone else’s claim.

The history of Jerusalem is a contested history. Debates about who deserved to live in the city and control it have persisted on and off since antiquity. Researching children’s books, especially ones used for educational purposes, provides insight into what was significant to society at the time of publication. What is omitted from texts like The Fall of Jerusalem is also significant. Sometimes, excluding certain information is deliberately done to suppress certain ideas. Even if the history of Jerusalem was taught in American schools or in religious contexts in the 1860s, finding credible works about the city translated into English would not necessarily have been simple. Hallock’s book might have been one of the only sources about Jerusalem available specifically for children in America. Prejudice or bias in a children’s book would therefore have serious ramifications.

For such a short book, it is relatively thorough. Hallock references biblical passages and relies on Josephus’ account of the city’s destruction for the bulk of the information. Unfortunately, Hallock does not cite any of the sources she used to write The Fall of Jerusalem, but we might make educated guesses about Hallock’s sources. In 1737, W. Bowley, a publisher in London, published a translation of Josephus’s work titled The Genuine Work of Flavius Josephus, by William Whiston. This translation of Josephus’s work included the first seven books of The Jewish War, making it a probable source.[11] Recently, the University of Oxford collaborated with the UK Arts and Humanities Council to create the “Reception of Josephus Project.” The project’s mission statement declares that “Josephus has been crucial in the formation of modern Jewish identity. Our project explores how Jews since the middle of the 18th century have used and recreated his writings and how they have built on earlier uses of them for their own purposes.”[12] Neither Hallock nor the American Tract Society was listed in this project, but it does include authors and texts written in English that could likewise have helped Hallock create her books – and her book certainly fits into the broader purview of the Oxford project to trace the reception of Josephus in the modern period. One of the authors mentioned in the “Josephus Project” was Anglo-Jewish author Grace Aguilar who, while being British, had a large audience in America. A contemporary of Hallock, Aguilar “often [chose] themes from Jewish history and religion, she sought to dignify Judaism and to push back Christian missionary activity.”[13] Aguilar died in 1847, meaning that The Child’s History of the Fall of Jerusalem was published after her death.[14] It is possible, however, that Hallock attempted to rewrite Aguilar’s Jewish narrative from a Christian perspective and thus to undo the effects that Aguilar’s work might have had on American views of Jerusalem’s history.[15]

The book ends with a hymn called “The New Jerusalem,” written by Charles Wesley, the Methodist movement’s English leader and acclaimed hymn writer.[16] The last stanza reads:

Jerusalem, my happy home!

My soul still pants for thee;

Then shall my labors have an end,

When I thy joys shall see.[17]

Ending the book with this hymn was another strategic move by Hallock and the American Tract Society because it reinforces the Christian narrative they cultivated throughout the book. In this narrative, Jerusalem is a heavenly city connected to the Christians. This hymn draws on and engages apocalyptic literature that suggests that Jerusalem is a destination before Heaven for Christians and a direct bridge to God. The hymn suggests that when Christians return to Jerusalem their struggles will end and they will be greeted by God.

Julia Kohut is a sophomore soon-to-be Political Science major and American Studies minor from New Jersey. She loves baking, reading, and learning about history.

This blog post was originally written for Prof. Sarit Kattan Gribetz’s “Medieval Jerusalem: Jewish Christian, Muslim Perspectives” course; the book and this essay will be featured in an upcoming exhibition at Fordham’s Walsh Library. We thank the anonymous donor who donated books from the Yosef Goldman Collection, which included the book featured in this piece.

Bibliography:

“American Tract Society.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 23 April 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Tract_Society. (Accessed December 9, 2020).

“Early History of the American Tract Society.” Internet Archive of the American Tract Society, 2008. (Accessed December 9, 2020). https://web.archive.org/web/20100525052409/http://www.atstracts.org/readarticle.php?id=4.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Charles Wesley.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Wesley. (Accessed December 9, 2020).

“First Judaica & Judaic Firsts: Works of Josephus.” Works of Josephus – Judaic Treasures. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/works-of-josephus-judaic-treasures. (Accessed December 09, 2020).

Galchinsky, Michael. “Grace Aguilar.” Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. 27 February 2009. Jewish Women’s Archive. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/aguilar-grace. (Accessed December 9, 2020).

Hallock, Mary Angeline. The Child’s History of the Fall of Jerusalem. New York: The American Tract Society, 1869. https://archive.org/details/childshistoryoff00hall/page/192/mode/2up. (Accessed December 9, 2020).

McClintock, John, and James Strong.“Hallock, William Allen, Dd.” The Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1880. www.biblicalcyclopedia.com/H/hallock-william-allen-dd.html. (Accessed December 9, 2020).

The Reception of Josephus in Jewish Culture. University of Oxford. January 12, 2020. https://josephus.orinst.ox.ac.uk. (Accessed December 9, 2020).

The Arch of Titus Project. Yeshiva University, https://www.yu.edu/cis/activities/arch-of-titus (Accessed December 17, 2020).

Rajak, Tessa. “Grace Aguilar.” The Reception of Josephus in Jewish Culture. The University of Oxford. August 27, 2015. https://josephus.orinst.ox.ac.uk/archives/605. (Accessed December 9, 2020).

[1] “American Tract Society.” Wikipedia.

[2] “Early History of the American Tract Society,” Internet Archive of the American Tract Society.

[3] “Hallock, William Allen, Dd,” in McClintock and Strong, The Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature.

[4] Hallock, The Child’s History of the Fall of Jerusalem, 23.

[5] Hallock, The Child’s History of the Fall of Jerusalem, 15-23.

[6] On the Arch of Titus, see “The Arch of Titus Project,” Yeshiva University: https://www.yu.edu/cis/activities/arch-of-titus

[7] Hallock, The Child’s History of the Fall of Jerusalem, 192.

[8] Image credit: VIZIN and the Yeshiva Univ. Center for Israel Studies; https://www.haaretz.com/archaeology/MAGAZINE-archaeologists-reconstruct-how-the-arch-of-titus-looked-in-full-color-1.5449144.

[9] Hallock, The Child’s History of the Fall of Jerusalem, 8.

[10] Hallock, The Child’s History of the Fall of Jerusalem, 11.

[11] “Works of Josephus.”

[12] “The Reception of Josephus in Jewish Culture.”

[13] Rajak, “The Reception of Josephus in Jewish Culture.”

[14] Galchinsky, “Grace Aguilar.” Some of Aguilar’s work Galchinsky mentions some of Aguilar’s writings, including History of the Jews in England; Israel Defended; The Jewish Faith; The Spirit of Judaism; Women of Israel; A Vision of Jerusalem, While Listening to a Beautiful Organ in One of the Gentile Shrines.

[15] Galchinsky writes: “Lacking any Jewish translation of the Bible into English, Aguilar often felt she could satisfy her religious yearnings only by going to hear sermons in Protestant churches. These church visits provided the material for one of her most moving and ironic poems, a reverie of Israel redeemed, entitled ‘A Vision of Jerusalem, While Listening to a Beautiful Organ in One of the Gentile Shrines.’ Her practice of attending church would later provide fodder for her critics. Missionaries claimed to be able to see the light of the gospel in her work; Jewish critics claimed she was a ‘Jewish Protestant.’ … Anna Maria Hall introduced her to Robert Chambers (1802–1871), the radical Edinburgh publisher of Chambers’s Miscellany, who solicited an essay from her entitled ‘The History of the Jews in England.’ This remarkable essay, published months before her death, offered a more radical vision of Jewish-Christian relations than Aguilar had dared to put forward in any previous text. Here Aguilar substantially rejected assimilationism and called English Christians to a more stringent account than she had ever done before.”

[16] Charles Wesley,” Encyclopaedia Britannica.

[17] Hallock, The Child’s History of the Fall of Jerusalem, 192.