by Jessica Roda, PhD, Georgetown University, Center for Jewish Civilization

Hasidic women are often portrayed in the mainstream media through a Western feminist framework, which assumes that women can only gain agency by leaving their faith. Two media events during the COVID-19 crisis have reinforced this narrative: The first is media coverage of the ultra-Orthodox response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its domination by male voices of rabbis, doctors, and male community leaders on various platforms, while women, such as journalist Efrat Finkel, are rendered invisible and unheard. The second event is the release of the Netflix drama Unorthodox, a miniseries based on Deborah Feldman’s 2012 memoir of the same name, which follows a hasidic woman named Esti, who can only end her suffering and shine as an artist by leaving her Brooklyn community for the secular, inclusive, multicultural, and artistic Berlin.

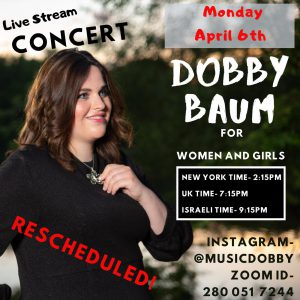

Although the ultra-Orthodox are known for their opposition to the Internet, some hasidic business owners find it necessary to be connected. Other ultra-Orthodox Jews use technology by choice. Among them are Dobby Baum, Malky Media, Devorah Schwartz, Sarah Dukes, Bracha Jaffe, Devorah Leah, and Chany Rosengarten, each of whom I discovered online in the last two years. These women come from a mixed ultra-Orthodox background, representing Bobov, Chabad, Ger, Litvish, and Satmar communities. They are particularly active on Instagram, where they promote their businesses, music, films, lessons, performances, and albums. The application serves as a marketing tool and springboard to create a community of followers. Ultimately, their use of Instagram might lead to their broader recognition, and to a range of contracts for live private and community performances. Dobby, Malky, Chany, Sarah, Devorah S., , Bracha, and Devorah L. are each building a new image of Orthodox womanhood. Implicitly, they are creating a counterpublic space (Hirschkind 2006; Fader 2020) in response to a mainstream religious space.

My intention is never to diminish the suffering of OTDs (Off the Derech, people who left ultra-Orthodoxy) or to dismiss the lack of action from some religious leaders, yet I felt the need to give voice to the Hasidic women whom I had the privilege to meet in person during my fieldwork and whom I follow on Instagram every day. To demonstrate the oversimplification of hasidic women’s agency, I would like to call attention to contemporary ultra-Orthodox women artists’ responses to the COVID-19 crisis.

Dobby Baum, March 2020 singing for her new single “It is meant to be”, Borough Park (NYC)

Malky Media at a tea shop (Brooklyn, NYC, January 2020)

Because modesty is central to their way of being, the majority of their activities occur live among only women and girls. The artists were preparing to perform and screen their films during Passover, but found their income compromised by the coronavirus outbreak. Like many around the world during this challenging time, they must fulfill their raison d’être by boosting their online presence and creating new opportunities for artistic collaboration.

During the pandemic, viral videos have surfaced of neighbors singing from their balconies in Italy, Spain, and France; songs such as “The Coronavirus Rhapsody”; and diverse compositions urging us to stay home and wash our hands. Similarly, Orthodox female artists have provided creative responses to the crisis online. They continue their women-and-girls-only performances via live concerts on Instagram and Zoom, where hundreds of girls and women participate from around the world. Their notable releases include their first collaborative video, “A Song for Lori,” in honor of Lori Kaye, who was murdered in the Poway synagogue shooting. Dobby Baum’s “It Is Meant to Be,” a response to COVID-19, is also noteworthy. As evidenced by their concert-conferences on Zoom, they have used this moment to constantly engage with their online viewers about the pandemic and the importance (and challenges) of staying at home. With thousands of followers––and more to come––they are reinforcing a sense of community and sisterhood. Crucially, they are reinventing their religiosity by means of technology and media. In doing so, they challenge narratives that imagine them as silent members of their religious society.

Postcolonial feminist scholars, such as Saba Mahmood and Serene Khader, have argued that critiquing Western secular feminism is necessary to prevent the oversimplification of the concept and experience of agency. Their argument is certainly relevant when it comes to the realities of conservative groups and families. These aforementioned scholars impacted how I understood my observations during my fieldwork with hasidic women in Montreal and New York City, and how I understand the online activity of ultra-Orthodox women artists.

The girls and women of Unorthodox cannot openly pursue their artistic aspirations. Dobby, Malky, Chany, Sarah, Devorah S., Bracha, and Devorah L. present a challenge to the show’s characters, as they seek new avenues to reinforce their religious belonging while challenging it from the margins.

Jessica Roda is an anthropologist and ethnomusicologist. She is currently an assistant professor of Jewish civilization at Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service. She is working on her second book, Beyond the Shtetl: Hasidicness, Women’s Agency and Performances in the Digital Age, in which she investigates how artistic performances empower hasidic and former hasidic women to act as social, economic, and cultural agents. Jessica Roda was a fellow at Fordham in 2017.