by Fabrizio Quaglia

A note from Magda Teter, the Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies: In November 2018, Fordham University acquired the Sefer Aburdarham published in Venice 1546 at an auction held by the Kestenbaum Auction House of some items of the important Valmadonna Hebraica collection, along with two other items. The book had been digitized by NLI before being sold. This year, as part of our work on an upcoming exhibition on history of censorship, we asked Mr. Fabrizio Quaglia, a Hebraica and Judaica consultant in Italy and an expert on Italian censorship of Jewish books to uncover the secrets old books hold within their pages. Part I explored a note in the upper left corner of the title page. Part II dealt with another note, on the printed ornate letters of the book’s title. Today’s installment deals with the marks left by Christian censors.

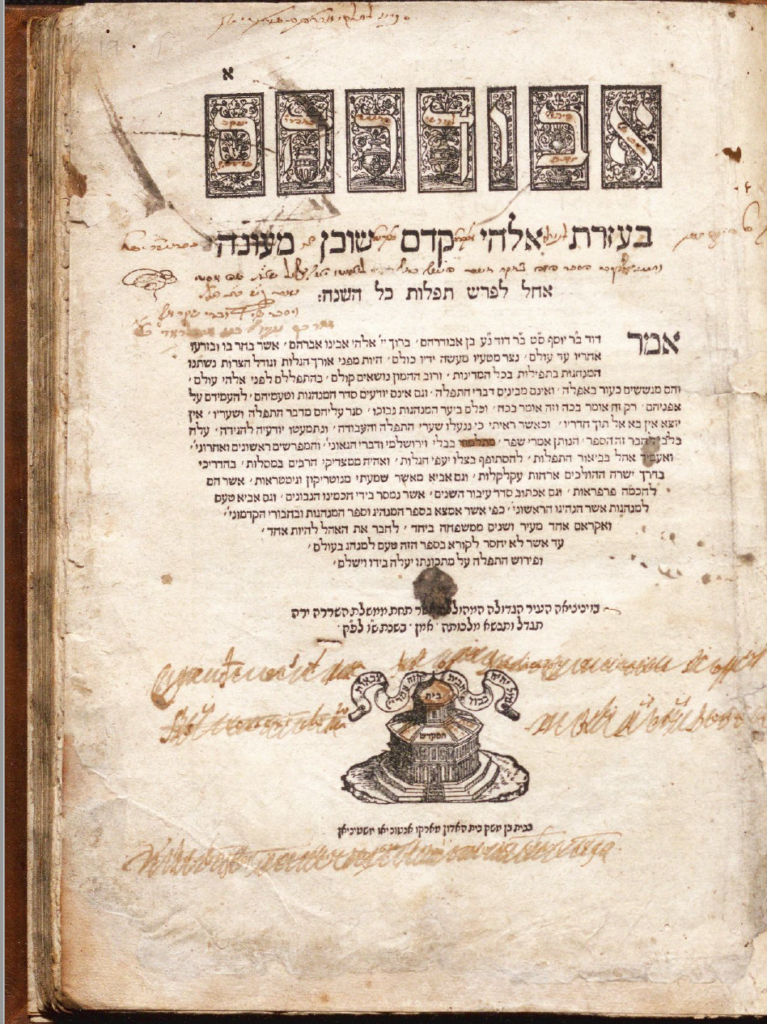

Next to the printer’s mark of Marco Antonio Giustiniani (with an image of the Dome of the Rock with an inscription בית המקדש “The Holy Temple” as a representation of the Temple of Jerusalem) is a crossed-out censor’s note “Ego fr[ater] vi[ncentiu]s de Ma[teli]ca fr.[ate]r or[din]is predicator[um] et vicarius s[anc]ti off[i]cij As[ten]is correxi de Ma[nda]to … R[everen]di p[atri]s inq[uisitor]is …” (“I, friar Vincenzo from Matelica friar of the Order of the Preachers and Deputy of the Holy Office of Asti, corrected by command … of the Reverend Father Inquisitor …). It is followed by another note, likewise crossed out, “Fr.[ate]r Jo.[annes] bap[ti]sta porcellus Inq.[uisit]or Asten.[si]s die. 15. 8bris 1590 (“Friar Giovanni Battista Porcelli, inquisitor of Asti, day 15 October 1590”). Similar inscriptions, almost verbatim, can be found in an Italian manuscript of the Tur by Jacob ben Asher now in the Palatina Library of Parma, Cod. Parm. 2901, f. [11]r.

The author of the first note, Friar Vincenzo da Matelica was born around 1550 in Matelica in the Marches (Central Italy), where he was apparently a rabbi (his Hebrew name is unknown) before converting to Christianity and becoming a preacher. His competence in Hebrew and rabbinic literature led him to become a professor of Hebrew, or as scholar Germano Maifreda put it “docente di lingua ebraica.” It is known that Friar Vincenzo was still alive in Ancona in August 1624 when he was 75 years old.

As shown by several of his notes for a period that spans more than thirty years, starting at least in 1590, the year of the note in Fordham’s Abudarham, Friar Vincenzo da Matelica became a censor of Hebrew books. In 1591, the inquisitor of Vercelli ordered Friar Vincenzo (and his colleague Paolo Visconte from Alessandria) to inspect books and manuscripts owned by the brothers “Aron et Lazzar Vitta Sacerdotti,” two Jews living in Vercelli. Ten years later, in 1601, “Vincentius” was returned to Vercelli. Other signatures prove that in in 1601 and 1602 Vincenzo da Matelica was also active in Pavia and was certainly a revisore of Hebrew texts in Ancona in October and November 1622 working together with friar Angelo Maria from Monte Bodio (a town near Ancona), who was a notary of the Holy Office. In Ancona, his work seems to have dissatisfied the Inquisition since texts he had already examined were reinspected six years later, in 1628, by a new censor.

The second censor, who left a now defaced signature on the title page of Fordham’s Abudarham, was Friar Giovanni Battista Porcelli (b. Albenga, 1534 – d. Asti, 31 January 1613). Friar Porcelli was the inquisitor in Alessandria (1572-1589) and Asti (1589-1613), where he was, as he tells in his book Scriniolum Sanctae Inquisitionism, apparently subjected to abuses and ridicule, as well as envy. In 1592, for example, he was ridiculed for trying to “revise” the whole Talmud, but later “his” Inquisition of Asti was recognized and praised in a letter from the secretary of the Congregation of the Index for implementation of Index by Pope Clement VIII.

Friar Porcelli was a zealous censor, eager to ban books even if they were not included in the Clementine Index of prohibited books. He frequently considered every book he deemed “heretical” book as worthy of not just of expurgation but of the stake. Besides giving his “imprimatur” to writings including those he himself authored, Porcelli printed in Asti in 1610 (but really in 1612) the lengthy manual for censors titled Scriniolum Sanctae Inquisitionis Astensis, in which he collected five sixteenth-century indexes of the so-called prohibited books that had been prepared by the Piedmontese Inquisition, including in Asti in 1576.

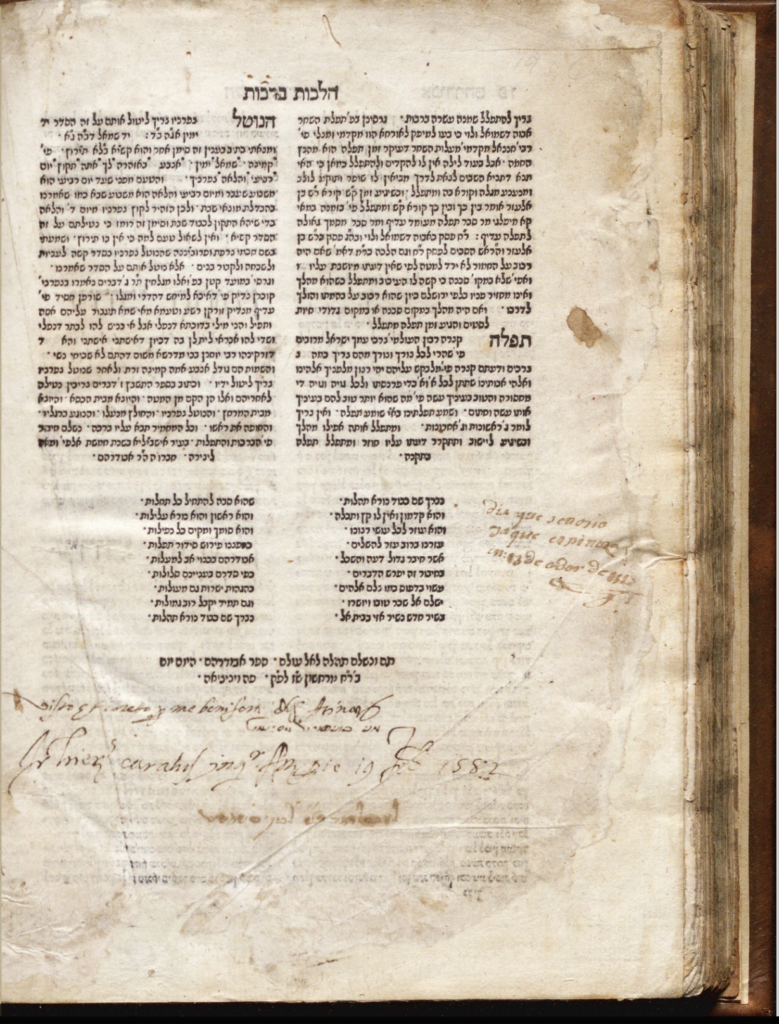

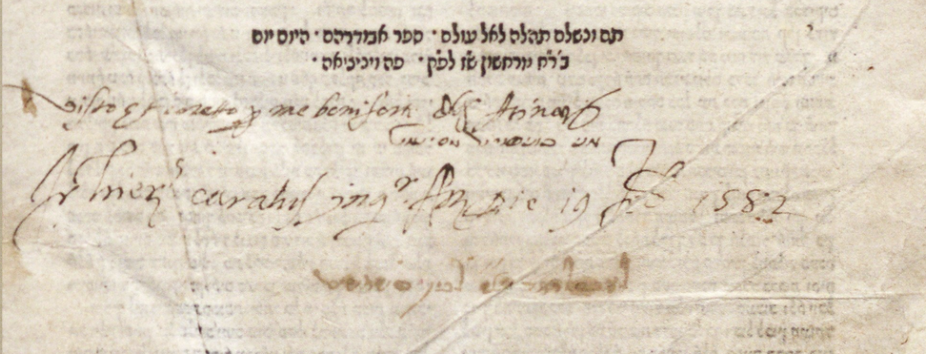

But there were also other censors who left their marks on Fordham’s Abudarham. After the colophon on f. 86v, there is the concise bilingual note “Visto et coretto p.[er] me Boniforte delli Asinari (“Checked and corrected by myself, Boniforte delli Asinari”) and אני בוניפורטי אסינארי (I, Boniforṭe Asinari”). This second signature in Hebrew suggests that Boniforte degli Asinari was a converted Jew, and not a Catholic man who studied Hebrew, since Catholic censors did not sign their names in Hebrew but converts sometimes did. For example, Domenico Gerosolimitano (formerly Shemu’el Vivas), a much better known expurgator than Boniforte degli Asinari, sometimes signed in Latin as well as דומניקו ירושלמי (Dominiqo Yerushalmi), that is a Hebrew transliteration of the surname that he assumed when he became Christian.

Since Fordham’s Abudarham bore a signature of Friar Porcelli who was an inquisitor in Asti, it is worth noting that two men named Asinari lived in Asti during the 1570s. Boniforte likely took a surname from his patron, one of the two Asinaris, since it was customary that a neophyte would take the surname of his patron. Consequently, although Boniforte delli Asinari never reported in his censor’s notes the place where he was active, it seems that he was active in Asti. This means that Fordham’s Abudarham would have been in Asinari’s hands in Asti. Nothing more about Boniforte Asinari is known beyond 1582.

This appears to be confirmed by the subsequent note on that page:

“Fr.[ate]r hier.[onymu]s caratus inqu[isito]r Ast[ensis] die 19 Feb.[ruari] 1582” (“Friar Girolamo Carato inquisitor of Asti, day 19 February 1582”). Girolamo Carato (also called Carati, Caratto and Carratto) was inquisitor at Asti from 1566 until his death on 6 December 1588; the abovementioned Giovanni Battista Porcelli, who left his signature on the title page of Abudarham, succeeded him. Carato’s Latin notes and signatures appear on a handful of Hebrew manuscripts, all of them dated between 15 and 19 February 1582; as well as on nine sixteenth-century books now in the BNU of Turin, signed in 1586 and 1587 by “Caratus.” Given the paucity of books inspected by Caratto, one might conclude that censorship of Hebrew books was not his main focus, and instead he was dedicated to the usual job of an official of the Holy Office, namely hunting witches, real or alleged dissenters, and other examples of heterodoxy, and that Boniforte Asinari only briefly overlapped with Caratto.

Abudarham was a popular medieval commentary on the liturgy that was based on much material collected from the Talmud and from other rabbinic sources, it is therefore not surprising that its editions have been censored. Since the Fordham copy of Abudarham had been published before the Talmud had been banned and before the establishment of the Index of Prohibited books and the office devoted to book censorship, this copy would have had to be expurgated should objectionable materials have been subsequently discovered.

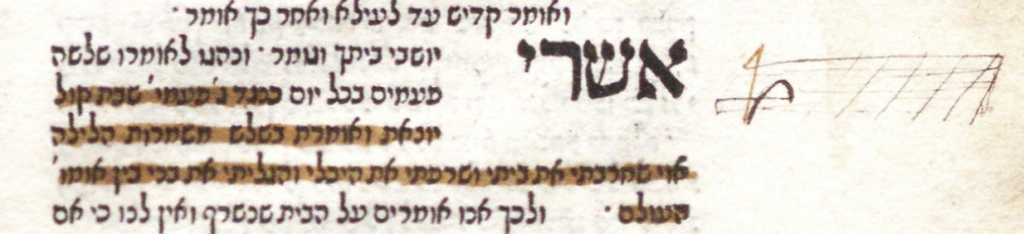

Fordham’s copy shows thin strokes of pen on around 30 folios, with the crossed out words still readable. Some of the expurgations were single words appearing on the title page like mi-Talmud (“from the Talmud”) and minim (“heretics”) while on f. 20r the sentence כעשתה התועבה הזאת בישראל (“that this detestable thing has been done in Israel”) taken from commentary to Deut. 17:4 and on f. 36v a longer line from the commentary by the author of Abudarham on the weekday prayers reciting after the Amidah (“The Standing Prayer”) were crossed out. Other words had corrected terms written above the expurgated words. For instance on f. 34r instead of Birkat ha-minim (“Blessings on the heretics,” part of the Jewish rabbinical liturgy that was considered as a Jewish curse of Christians) had Birkat resh`aot (“A blessing on the wicked”) written over—the word “minim” that was considered objectionable. Elsewhere the presence of those words was signaled on the margins by a vertical dash and sometimes by question marks. Those substitutions that aimed at eliminating every possible anti-Christian allusion in the text (see the abovementioned Birkat ha-minim) were most likely made by one of the Christians censors and not by the book’s Jewish owners. But who may have decided to make those markings? We can exclude Asinari since his Hebrew calligraphy is different, moreover he used a black ink while the questioned words have been penned in red. Without chemical analysis it is difficult to tell who is responsible for the expurgations.

In the next and final installment, we will circle back to the question of ownership to explore to whom the book belonged over the centuries.

A note from Fabrizio Quaglia: I thank Dr. Alexander Gordin, paleographer and staff member of the National Library of Israel, for helping me render some of the Hebrew signatures on Fordham’s copy of Abudarham. Dr. Fabio Uliana, Office of Ancient Funds and Special Collections, Protection, Conservation and Restoration of Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria of Turin, for sending images of BNU books, and Dr. Alberto Palladini, Archivist of Archivio di Stato di Modena for checking for me the list of Leon Poggetti’s books, where this document is located.

Fabrizio Quaglia is Hebraica and Judaica Consultant. His last publication is Il recinto del rinoceronte. I giorni e le opere degli ebrei ad Alessandria prima dell’emancipazione del 1848, Alessandria, Edizioni dell’Orso, 2016. Editor of MEI: Material Evidence in Incunabula Editor: https://www.cerl.org/resources/mei/about/editors.