Sophie Hamlin FCRH’22

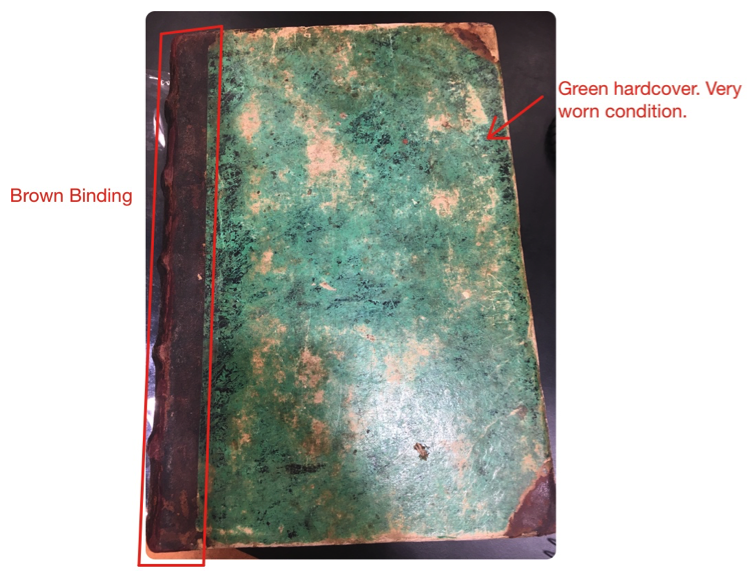

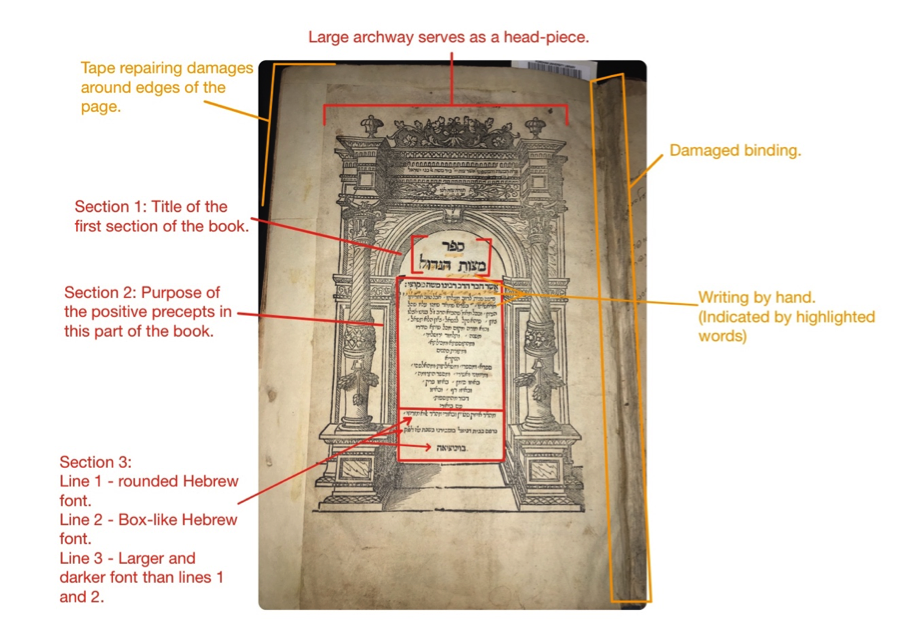

Measuring only 4.5 by 5.5 inches, the French and Hebrew prayer book Sidur Minhat ‘Erev[i], is not eye-catching in the slightest. It has a plain, peach-colored cover, void of any markings beside those accidentally added over time. The binding is falling apart but the pages are in good condition, suggesting that while this book was certainly used, it may not have been the well-loved, well-worn prayer book carried everywhere with a person. It appears to be cheaply made and boasts no grandeur in the slightest. However, this book can shed an interesting light on the life of Jews, specifically French-speaking Jews living in Cairo at the time of World War II.

This prayer book was published in 1943 in Cairo, Egypt by the publisher Editions Dath. It is a Jewish prayer book meant specifically for everyday use and the Sabbath as is described in the subtitle “Pour la semaine et le samedi”. It contains prayers written in Hebrew characters juxtaposed against French translations of the same prayers. There is no available information as to who precisely translated this prayer book, other than the ambiguous note “French translation by a group of rabbis”. In fact, the only name actually mentioned is that of Rabbi Dr. Moses Ventura, the chief rabbi of Alexandria (1937 – 1948), who wrote the French foreword to the text. Upon further research, there appears to be only one other reference to Rabbi Ventura on databases available at Fordham. In the footnotes of Dr. Nadia Malinovich’s PhD dissertation “Le Reveil D’israel: Jewish Identity and Culture in France, 1900 – 1932,”[ii] there is a reference to another book in which a man named Moishe Ventura wrote a foreword.[iii] Rabbi Ventura’s involvement in the two books book illustrates the vibrancy of the Egyptian Jewish community in the early-mid 20th century. Although the Sidur Minhat ‘Erev had limited circulation throughout Cairo, it still contained a foreword from the chief rabbi of Alexandria, a rabbi who had two works published in French, evidencing the widespread influence of French schooling in Egypt.

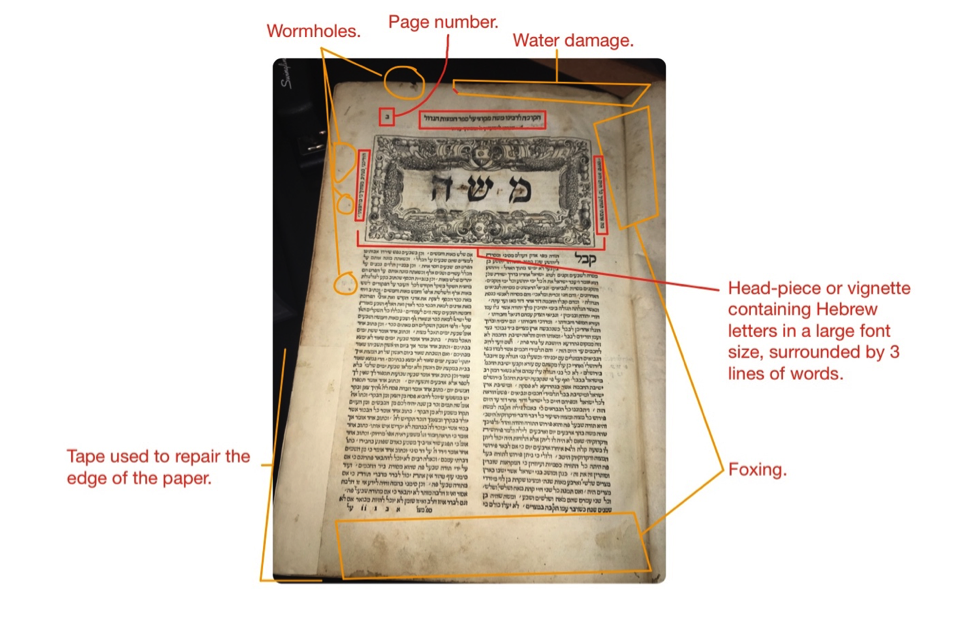

Another mystery lies in the publisher of this prayer book, Editions Dath. Editions Dath appears not to have published any other books, at least none on record. In fact, even the book at hand, Sidur Minhat ‘Erev, has only two recorded copies in the world. One at Fordham University and the other in The National Library of Israel[iv]. However, the lack of information concerning the publisher can actually reveal quite a bit about the circumstances of this book’s publication. It is more than likely that only one edition of these siddurim was ever circulated, due to the lack of surviving copies. Furthermore, it is clear that the printing was done cheaply, as many pages are printed quite crookedly.

The book was printed specifically for the French-speaking Jews in Cairo, not for a large-scale audience, and Editions Dath was likely a publishing company set up by those in this community, influenced by schools founded by the French. The question remains, who precisely made up the French speaking Jewish community in Cairo? While one could a group of French immigrants, more likely it was educated Egyptian Jews. In the 20th century, many Cairo Jews went to French schools established by Alliance Israelite Universelle. According to Joel Beinin, “… the use of French in the community schools [was] a result of the proselytization of the Alliance Israelite Universelle”[v]. Alliance Israelite Universelle, a French Jewish organization focused on educating Jews in the Balkans and the Middle East on Jewish and French culture,[vi] came to Cairo around 1903. By the time this siddur was written, French was the language being taught in schools to most Sephardic Jews. Consequently, this prayer book could be used not only by the French Jews in Cairo, but by all French speaking Sephardic Jews.

This book is not ornate; it has no pictures and is in mediocre condition. There are water stains throughout and, as earlier mentioned, is falling apart at the binding. This is not the book of a religious official, nor a remarkably wealthy man. This is the book of an average man, leading one to conclude that even the average man at the time spoke Hebrew. (It is clearly a man’s book because women at the time could not practice religion in the same way. This is evidenced by the distinct lack of mention of female prophets in prayers such as the Amidah, as is common in traditional Sephardic practice.)

The book in Fordham’s Special Collections likely belonged to an average, yet educated Cairo Sephardic man. The font is large enough that it can be assumed the book was meant for personal use. However, there is a distinct lack of transliteration meaning that either a) the intended user spoke Hebrew or b) simply would follow along with the French translation as the rabbi conducted a service.

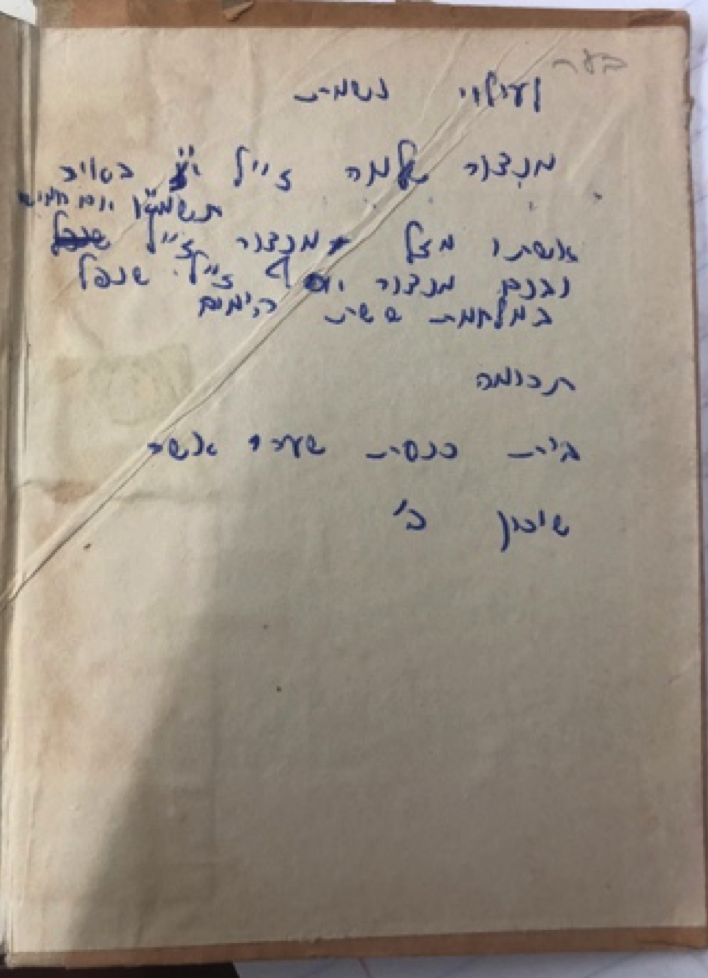

On the inside the front cover of this copy of Sidur Minhat ‘Erev at some point the owner wrote a note in Hebrew script about the owner’s migration to Israel with the book. The book was owned by an Egyptian family Mansour (Mantsur), and was still used after they migrated to Israel. Hebrew notes on the inside cover demonstrate that the owner of this book spoke Hebrew, at least after he and the family moved to Israel.

Published in 1943, the book appeared at the height of World War II, soon after the Allied defeat of the Nazis in Egypt. In the 1940s, Egyptian Jews appear to have published other texts: at least two Haggadot,[vii], another siddur,[viii] and a fiction book.[ix] To contrast, WorldCat only revealed one French Jewish text originating in Cairo outside of that era – a siddur written in 1917.[x]Jews in Cairo were thriving in the early 1940s, and yet they were so close to a mass exodus out of Egypt.[xi] It is remarkable that just years before many of the Jews left for Israel, they were a thriving, intellectually stimulating community living with enough stability to produce a number of books.

An interesting picture is painted of 1940s Jewish Cairo. It seems to be a productive, educated community, and yet it is only a few years away from a major disruption. The fact that many would have spoken not only Arabic but, also French and Hebrew points to a level of literacy higher than average. The number of surviving volumes from this era also shows the emphasis placed on furthering Jewish education. This small, 213-paged, peach-colored book originated, Sidur Minhat ‘Erev, which, stand-alone, is certainly quite obscure, actually has much to tell about World War II era Cairo, and offers a glimpse into the lift of Jews there.

This essay was written in fall of 2018, during Sophie Hamlin’s first semester at Fordham, within a course on modern Jewish history (HIST 1851) taught by Professor Magda Teter. Their essays, some of which will be featured here, were published in a volume “You Can Judge Books by Their Covers Jewish History through Used Books.” Fordham’s Judaica collection prides itself in collecting books that were used and popular, often quite quotidian and ordinary, for they reflect a broader Jewish culture that might not be visible through expensive extraordinary items.

[i] Sidur Minḥat ʻerev: Minhav Ṿe-ʻaravit = Office De Preières: Min’ha Et ‘Arbit (Pour La Semaine Et Le Samedi). וערבית מנחה: סדור מנחת ערב = Office De Preières : Min’ha Et ‘Arbit (Pour La Semaine Et Le Samedi) / Traduction Francaise Par Un Groupe De Rabbins. Le Caire : Editions Dath, ©1943.

[ii] Nadia Donna Malinovich, “Le Reveil D’israel: Jewish Identity and Culture in France, 1900–1932 – Proquest” (Web, University of Michigan, 2000).

[iii] Judah Ha-Lévi, “Le Livre Du Kuzari,” Bibliothéque nationale de France. Département des Manuscrits. Hébreu 757 .

[iv] וערבית מנחה : ערב מנחת סדור, 1 ed. (Le Caire: Editions Dath, 5704 – 1943).

[v] Joel Beinin, The Dispersion of Egyption Jewry: Culture, Politics, and the Formation of a Modern Diaspora(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998).

[vi] “Alliance Israelite Universelle,” Encyclopaedia Judaica. © 2008 The Gale Group, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/alliance-israelite-universelle.

[vii] Hagadah Shel Pesah :Ke-Fi Minhag Sefaradim = La Haggadah De Pessach a L’usage Du Rite Sefardi (Cairo, Egypt: Feliks Mizrahi, 1945); Hagadah shel Pesah kefi minhag k”k sefardim im targum aravi be-otiyot araviot (Cairo: Hotsaʼat ha-Mizraḥ, 5706 [1945 or 1946]), SPEC COLL JUDAICA 1946 1.

[viii] Alexandre Créhange, Sidur Sha`Are Tefilah (Cairo, Egypt1946).

[ix] Segulah:Le-Hantsal Hu U-Vene Beto Min Ha-Sakanah Umi-Mikrim Ra`im (Cairo: Defus Yosef Yehezkel, 1940).

[x] Hillel ben Jacob Farhi, Siddur Farhi, 4th Edition ed. (Wyckoff, NJ; Cairo, Egypt2003, 1917).

[xi] Beinin.