by Paula Ansaldo, University of Buenos Aires

During the twentieth century, the city of Buenos Aires was one of the main centers of Jewish culture and theatre. The great Yiddish theatre began to flourish in the 1930s when Buenos Aires was established as a Jewish theater city of international relevance. During the interwar period, a large population of Yiddish-speaking Jews settled in Buenos Aires, escaping from European hard living conditions and anti-Semitism. As a result, a rich Yiddish cultural life began to grow, and the city became an attractive destination for intellectuals and artists.

At the same time, by the 1930s, the audiences of the Yiddish theatre in the US were already declining, so the actors and actresses decided to go touring to other countries where the Jewish communities were still eager to see theatre in Yiddish, as it was the case of Argentina. The southern hemisphere had an extra advantage: it benefited from the season’s opposition. This allowed that during the summer break the actors could go to work in Argentina, without the need to completely leaving their own companies. That way, they were able to do two winter seasons: one in the US and another one in South America, one based in New York, and the other one based in Buenos Aires, from where they also traveled to other Argentinean cities, such as Rosario, Córdoba, and Santa Fe, and to the Jewish colonies, as Moisesville and Basabilbaso. They also tour other Latin American cities, such as Montevideo, Santiago de Chile, Sao Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro. This way, many American Yiddish theatre directors and actors, came to Argentina and their work had a profound impact on Buenos Aires’ theatre scene.

Between 1930 and 1950, the golden age of Jewish theatre in Buenos Aires, four theatres presented plays in Yiddish regularly: the Soleil and the Excelsior (in the Abasto), the Mitre (in Villa Crespo), and the Ombú (which is where the AMIA is today). In addition to the theatres, some cafes also presented Yiddish vaudeville numbers, such as the Cristal and the Internacional, creating a wide Yiddish theatre scene. The shows were held from Tuesday to Sunday, even with two or three performances on the same day during weekends. The season normally lasted from April to November. And the theatres had always a full house.

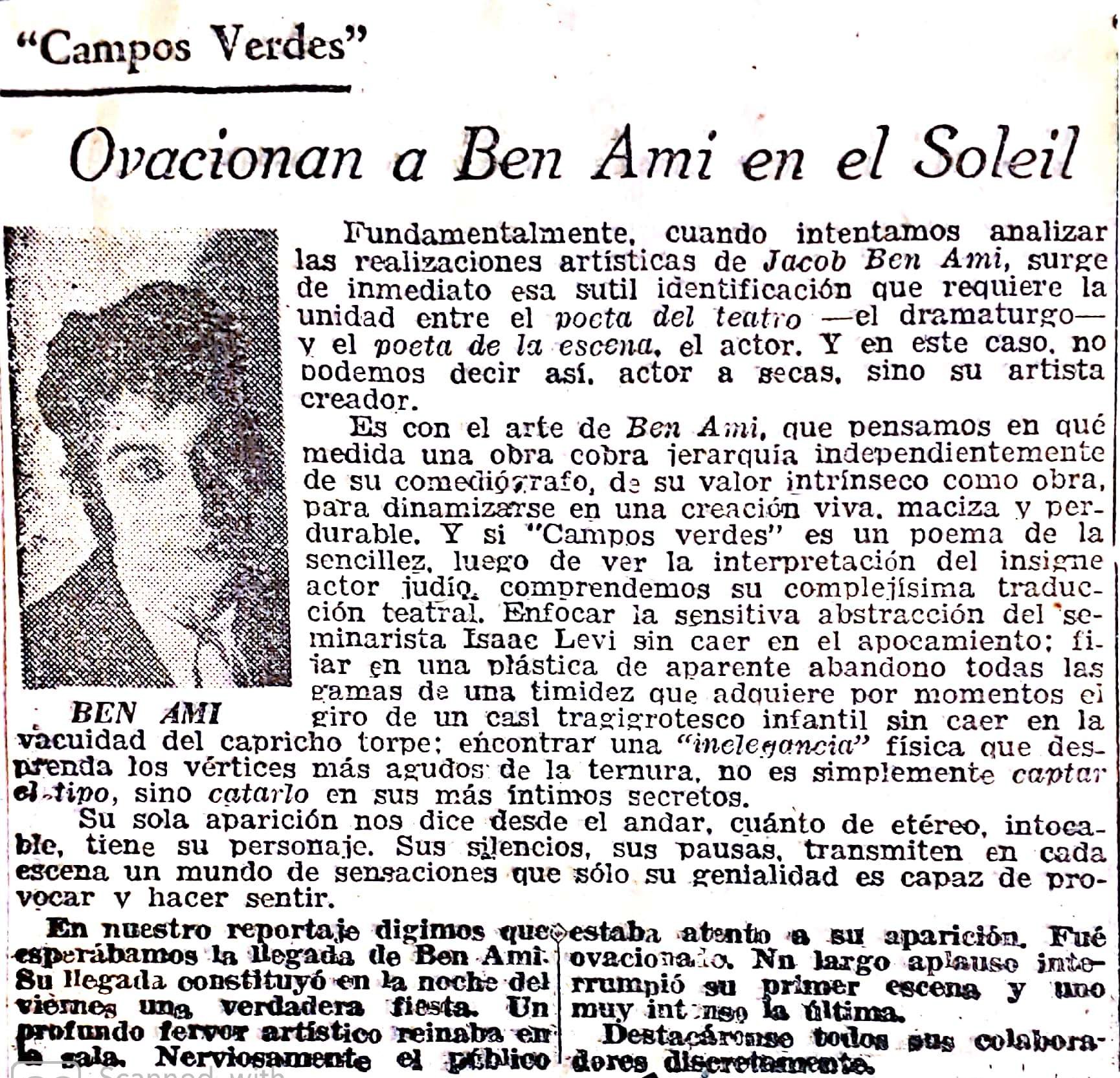

The Commercial Theatre in Buenos Aires was organized by a star system. The impresarios brought stars from abroad to lead their companies and completed the cast with local actors and actresses. Thanks to this guest star system, many renowned artists arrived in Argentina and were considered outstanding visits even outside the Jewish theatre community. This happened especially in the case of the actors Jacob Ben-Ami, Maurice Schwartz, and Joseph Buloff, whose repertoire and acting style were completely different from the type of plays (like operettas, melodramas, and light comedies) that prevailed in the theatres of the period, Jewish and non-Jewish also. Anyone who looks into Argentinean newspapers will probably be surprised by the way the theatre reviewers wrote about these Jewish actors. In most cases, the critics didn’t even mention that they were performing in Yiddish. Instead, they focused on their acting skills and abilities, and referred to them as figures of universal theatre, regardless of the language they were using on stage. Many sources show that the critics and actors of the non-Jewish theatre went to see Yiddish plays and were admires of these Jewish actors. The actress Silvia Parodi, for example, says about Ben Ami:

Ben Ami has the gift of making himself understood without the need for language. (…) even without understanding a letter of the text, it’s enough to contemplate his face to feel all the passions and feelings reflected. Silence, attitudes, gestures, say so much that there is no need for more to understand him and admire him.

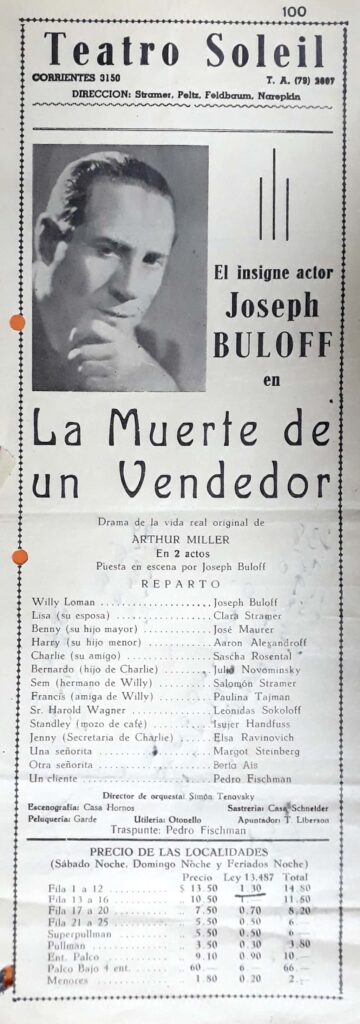

Therefore, the Jewish theatre was seen by the Argentinean community as a significant phenomenon, especially when the actors brought repertoire that was unknown in the Buenos Aires theatre scene. This was the case of Joseph Buloff’s Death of a Salesman/Toyt fun a seylsman, which premiered in Buenos Aires in 1949 in Soleil Theatre. This was the first time that the Argentinean public saw an Arthur Miller’s play. The show was such a success among Jewish and non-Jewish audiences that in 1950, the prominent actor Narciso Ibañez Menta premiered a Spanish version of the play. This is an emblematic case that shows how the Yiddish Theatre operated as a modernizing force that deeply influenced the theatre scene of Buenos Aires. Its itinerancy enabled, through the use of Yiddish language, the arrival of radical theatrical ideas, modern aesthetics and new repertoires that had not yet been translated to Spanish and neither developed in Buenos Aires’ theatres.

For these reasons, my time researching at the Dorot Jewish Divison at the NYPL help me to gain a better understanding of the transnational Yiddish theatre network and the connections established between Argentinean and American Yiddish theatre. NYPL materials regarding Joseph Buloff and Ben-Ami allowed me to improve my understanding of their artistic conceptions and how their artistic background, acting style, and repertoire influenced and shaped the Jewish theatre of Buenos Aires.

Paula Ansaldo is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Buenos Aires. In the fall of 2019 she was a Fordham-NYPL Fellow in Jewish Studies. On October 3, 2019 she delivered her talk about ” “A history of the Jewish Theater in Buenos Aires: from the star system to the Idisher Folks Teater (1930-1960),” which can be viewed below.

Paula Ansaldo, “A history of the Jewish Theater in Buenos Aires: from the star system to the Idisher Folks Teater (1930-1960)”