Fordham’s Center for Jewish Studies is thriving on campus; last year, the Center celebrated its fifth anniversary. But before the formal founding of the CJS, many professors, students, librarians, and others taught, studied, and cultivated the study of Jews, Judaism, and Jewish history and culture at Fordham. This blog series features interviews with some of these people and celebrates their lasting contributions to the university.

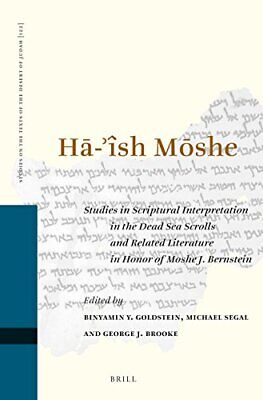

This interview features Professor Moshe Bernstein, who taught Biblical Studies at Yeshiva University. Professor Bernstein received his M.A. in Classical Languages from Fordham in 1968 and then his Ph.D. in Classics, also from Fordham University, in 1978, while also studying at Yeshiva University. He was the inaugural holder of the David A. and Fannie M. Denenberg Chair in Biblical Studies when he retired from Yeshiva University at the end of the 2022-23 academic year.

Can you tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do?

I just retired from Yeshiva University, where I taught for many years at both Yeshiva College and Stern College. I received my Ph.D. in Classics from Fordham in 1978, but at Yeshiva University I taught primarily Biblical Studies, some Second Temple intellectual history, including Dead Sea Scrolls, and Biblical Hebrew and Aramaic.

My research areas started out in Aramaic targumim (Aramaic translations of the Bible), about which I was going to write a never-finished second PhD thesis at Yeshiva. But then someone suggested to me that the Dead Sea Scrolls would sell better, and I started working in that field. In 2012, I published a two-volume collection of my essays called Reading and Rereading Scripture at Qumran, which includes almost everything I wrote about the scrolls over a thirty-year period. I’ve also published a number of articles about Aramaic targum, and I’m currently working on Aramaic liturgical poetry of the Byzantine period, much of which remains in manuscripts from the Cairo Geniza and hasn’t been published. Now that I’ve stopped teaching, I can focus on editing and publishing my unpublished work in those areas. I’m currently also working on a book with one of my colleagues at Yeshiva which will present the literary texts in Aramaic from the Dead Sea Scrolls along with their translation into English on facing pages, in the fashion of the Loeb Classical Library in Latin and Greek.

What about your family?

My maternal grandfather was a Hungarian immigrant who came to New York after World War I. His daughter, my mother, was a life-long educator, whose career culminated with many years as a teacher and guidance counselor in the NYC public school system. My father was a talmid muvhak (outstanding student) of Rav Moshe Soloveichick. He served as a congregational rabbi for some time after being ordained, but returned to YU as a faculty member around the time I was born. He gave a shiur [a Talmud class] in the morning and then taught Jewish History, Hebrew, and Bible in the afternoon. He climbed the ranks and eventually became a Rosh Yeshiva and subsequently taught at the Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies, primarily Semitic languages. He had many students who became scholars and rabbis. My wife is retired now, but she also started out as a Classicist and then eventually became an academic administrator most recently in the art school at Cooper Union.

You first came to Fordham as a student in the 1960s. What brought you to Fordham, and what was it like at the time?

When I studied Classical Languages at Fordham, my professional goal was to be an academic Classicist. I was learning for semikha, rabbinic ordination, at RIETS and studying for a Masters in Semitic languages at Yeshiva University during the same period, but the twain never really met. It was an interesting choice that I made to come study at Fordham, but some of it had to do with which program in New York gave me the best fellowship. Because of my studies at Yeshiva, I was limited to NYC.

What courses did you take and what do you remember about your time on campus?

It was a regular Classics Department, and fairly laid back. There were many people with whom I really enjoyed studying. I remember studying with Father Richard Doyle, Father Edwin Quain, and Father William Grimaldi. I had a good number of courses with each of them. And then there were others along the way, with whom I studied various topics in Latin and Greek literature. Father Herbert Musurillo was a Classicist as well as a student of the Church Fathers. He gave me a copy of a Greek text that he edited by Gregory of Nazianzus. I took courses in Medieval Latin and paleography, and other things that I might not have studied in other departments, and those were both interesting and proved useful over the years. I was fortunate to have a good background because of my teacher at Yeshiva, Louis H. Feldman, z”l.

The student body was heavily Catholic. Many of my classmates went on to be high school teachers. A few continued to get their Ph.D.s and have by now retired from their posts as well. The atmosphere was a regular academic atmosphere, except for the crucifixes on the walls, which came with the territory. My mother, z”l, was once asked, “aren’t you worried about Moshe going to Fordham?” She said, “No, I’m worried that the nuns are going to start saying Mincha [Jewish afternoon prayers].”

What was the topic of your dissertation?

It took me a long time to finish my dissertation, which was typical in those days. I did a literary study of a Euripidean play, The Trojan Women. Some time later, when I was teaching Eichah [the biblical book of Lamentations] one year at Yeshiva, one of my students, an unusually well-read young freshman, raised his hand and said, “Could you comment on the similarities between Eichah and Euripides’ Trojan Women? I said, “You know, I’ve been waiting years for somebody to ask me that question.” I even had index cards someplace with notes on the comparison, because I had thought about it. You’re dealing with two literary works on the aftermath of war, so the parallels and similarities become obvious after a little thought. I spent 15 minutes talking about something I never thought I would be able to talk about only because of that well-read freshman at Yeshiva College.

We recently inaugurated the Bronx Jewish History Project, a collection of oral histories and documentary sources about Jewish life in the Bronx in the long twentieth century. You grew up and lived in Washington Heights, but you came to Fordham’s campus for your studies. What was the Bronx like at the time?

I got on the 38 bus at 181st St. and Amsterdam Avenue, took it to Fordham Road, then took the 12 or the 19 to Fordham. And that’s all I saw of the Bronx.

What do you remember about the Jesuit and Catholic character of Fordham, and how did it impact you as a Jewish student?

I was very much a commuter student during my graduate years; my mornings were devoted to Torah study at RIETS and my late afternoons to Latin and Greek. I think that I was the only Jew in the Classics department, but was never treated as a curiosity. The department accommodated my scheduling needs so that courses that I had to take were never scheduled on Friday afternoon or Saturday. I usually didn’t take any 3 PM classes, because Rav Soloveichik’s classes ended at 2:30 PM and it was too tight to make it to Fordham on time. I was literally going from the Beit Midrash to the library at Fordham, but it was quite comfortable in that regard. It was a good place to be. They wanted me to feel okay.

I remember being worried because the last fall course that I had to take was scheduled at a time when I would need to miss the first three or four class sessions because of Jewish holidays. The instructor was a professor from Germany, and I was worried about how he would react to my repeated absences. It turned out that he was a liberal post-World War II German, and we got along fine.

I distinctly remember, during the first summer that I attended Fordham, informing my instructors that I would be attending class on the fast day of Tisha be’Av, but would appreciate not being called on. I had gone to shul early in the morning but hadn’t finished reciting qinot (lamentation poems recited on Tisha be’Av), so between my two graduate courses, I finished reciting qinot on the lawn outside the library.

Classes often began with a prayer, and I had an elderly German professor, an Augustinian monk, who still prayed in Latin. He had been born in the late 19th century, and by the time I had him as a student in the late 1960s he was no longer a youngster. He was a specialist in Greek and Roman religion, and one day he proudly wrote out for me a couple of words in block Hebrew script, to show me that he could read Hebrew. It was actually a very nice gesture. Life was a bit more formal back then, and I wore a jacket and tie to class. Once on a warm fall day, when I took off my wool blazer, I was gently told by my distinguished Jesuit instructor, “We do not do that here.”

For someone whose education had been almost exclusively in insular Orthodox Jewish institutions, the Classics department with its largely Catholic, and often clerical, student body, was a valuable exposure to the “outside” world that probably has benefited me considerably in later academic life. It was a great eye opener to work in the real world. Not that Fordham was so much the real world either, but it was a different world from the world of yeshiva and classical Jewish educational institutions. In that way, it prepared me for interacting with colleagues who had radically different backgrounds from mine. I suspect it smoothed out some rough edges and prepared me to go to SBL [the Society of Biblical Literature conference] and hang out with the rest of the crew there.

What did you do after you graduated? Did you end up teaching Classics or Bible or both?

I taught Classics at the University of Illinois – Chicago for five years before completing my Ph.D. thesis (it was possible to get a job before finishing back then). By the time I finally completed my dissertation, the job market in classics had dried up and I came to realize that my strengths in Jewish Studies and Bible offered me a different point of entry into higher education. I then found myself back at Yeshiva University a couple of years later teaching Bible and Second Temple, while working on a Ph.D. in Bible that I never finished (although some of that research has been published).

I’ve taught a variety of courses in Bible, biblical interpretation, Second Temple intellectual history, Hebrew and Aramaic at Yeshiva over the last 40+ years. At the beginning of my YU career, I taught a few courses in Latin and Greek when Professor Feldman was overloaded and they needed someone to teach a course, but they were never a main component of my workload. I’ve certainly been able to take advantage of my training in Latin and Greek in my research in early biblical interpretation, but that is only loosely connected to my work at Fordham. If I have to look at a Septuagint or at Josephus or Philo or Jerome in the Vulgate, those are all things that are readily at hand for me.

Once you’ve done work in literature in a language that isn’t your own, you can move far more easily from one language to another. So for me, moving from Latin or Greek poetry into biblical poetry felt natural and complementary. I remember when literary studies were just starting out in Biblical Studies, when Robert Alter published The Art of Biblical Narrative in 1979 and James Kugel published The Idea of Biblical Poetry in 1981. In a certain sense, I was a step ahead because I had been doing this stuff already in the field of Classics, and it was just a question of finding out what was going on currently in the field. In many ways, my teaching was separate from my research, but when I taught Biblical Studies, I was able to draw on literary studies. It made teaching a lot of fun.

You were a regular member of the Columbia Bible Seminar, alongside faculty members in the field from New York, including several Fordham professors. How did you get involved in the seminar?

I forget who it was who realized that I was teaching Bible at YU and invited me. They tried to cast a wide net, and if you teach Bible and you’re in the New York Metropolitan area, you’re invited. I used to attend the seminars whenever I could, and ride back to Teaneck with Steve Garfinkel, who was the Associate Dean at the Jewish Theological Seminary. I spoke there on a number of occasions, usually about the Aramaic versions of the Bible or about biblical interpretation in the Dead Sea Scrolls, because the definition of what counts as Hebrew Bible in that seminar is very generous. It was another place where I got to belong to a community that was different from my own home base. That’s where I got to know Mary Callaway, a Protestant scholar who taught Hebrew Bible at Fordham for many years, because we would occasionally sit next to each other.

Did Fordham impact your later work?

My Fordham education perhaps had an indirect effect on my later scholarly career. The study of ancient texts in Greek and in Hebrew or Aramaic is very similar, once you get beneath the surface. Some of the specialized courses like Paleography and Textual Criticism, although they focused on Greek and Latin texts, were readily applicable to some of the textual material that I have studied, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls and later Aramaic texts as well. The training and methodology I received in reading Greek and Latin literary texts transferred easily to the study of ancient literature in other languages. And the intellectual discipline that Fordham’s program in classics demanded has certainly served me well in a variety of aspects of my work.

Any thoughts about Jewish Studies @Fordham as we celebrate its fifth anniversary?

I admit that, based on my experience at Fordham more than a half century ago, I could not have imagined the program that you have developed. It gives me great pleasure to celebrate the creative leadership of your program and I look forward eagerly to learning about new initiatives.

Thank you, Professor Bernstein, for sharing these memories with us!