By Yael Levi, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

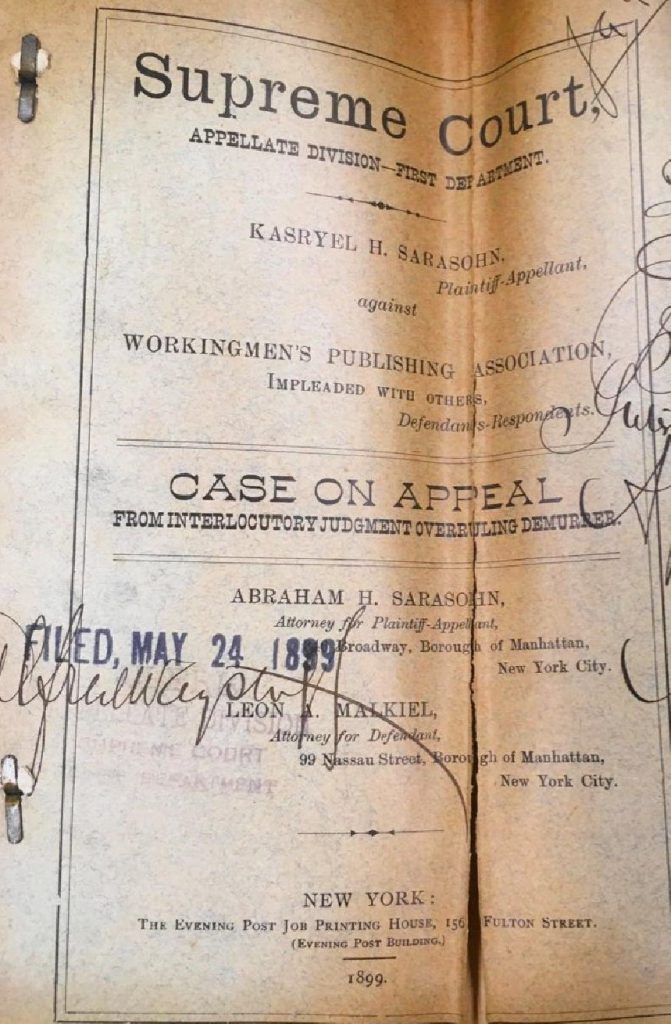

On August 22nd, 1898, the Jewish-Russian journalist Phillip Kranz, pseudonym of Jacob Rombro, received a subpoena from the Supreme Court of New York City. Kranz and other writers and editors of the “Workingmen Publishing Association” learned that “the action is brought to recover damages for libel, for a willful, reckless and atrocious libel.” The plaintiff was Kasriel Hirsch Sarasohn, the most important Yiddish and Hebrew press publisher in New York at the time. Sarasohn was represented by his son Abraham, a young and successful lawyer.

The trial revealed some of the most fundamental tensions in the Yiddish press in 1890s New York: orthodox versus secular; capitalism versus socialism; a family business versus a workers‟ organization, popular journalism versus cultural elite journalism, etc. All of these tensions presented themselves openly.

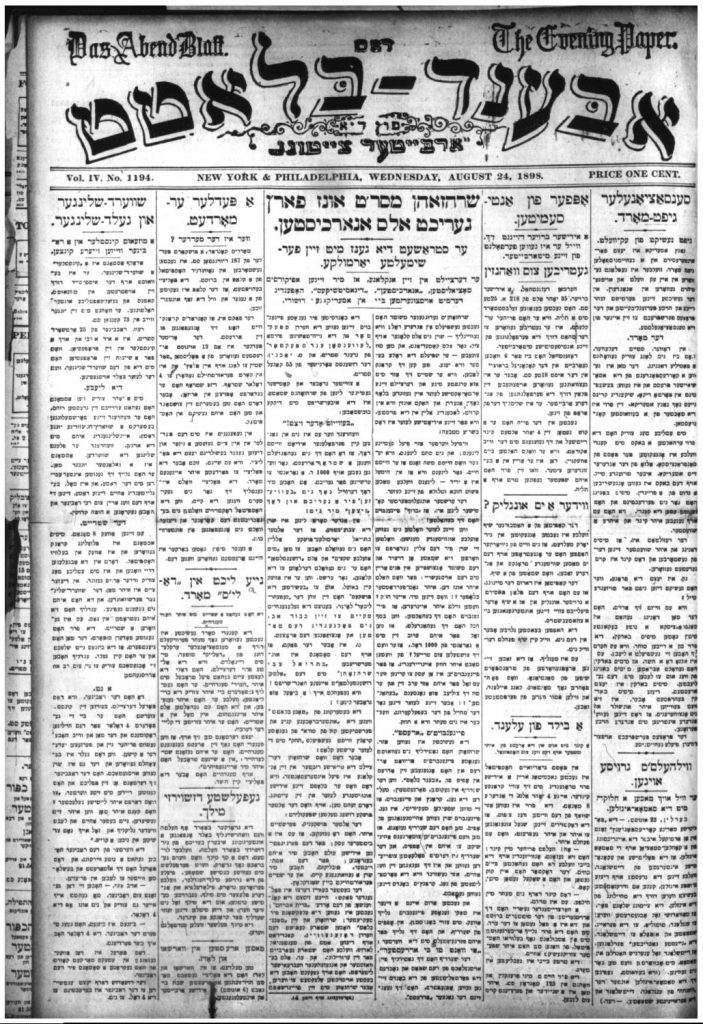

The cause for Sarasohn‟s complaint was an article from the socialist Yiddish daily “Dos Abendblatt” (The Evening Paper; founded in New York on 1894). The socialist daily had been attacking Sarasohn for months, publishing one investigation after another about his misuse of charities, as well as misrepresenting himself as a friend of the workers‟ class supporter, a supporter of the Zionist cause, a charity organizer – thus gaining support, good reputation and capital – while using them eventually for his own profit. Sarasohn demanded 20,000 dollars for the damage to his reputation within the Yiddish speaking community in New York.

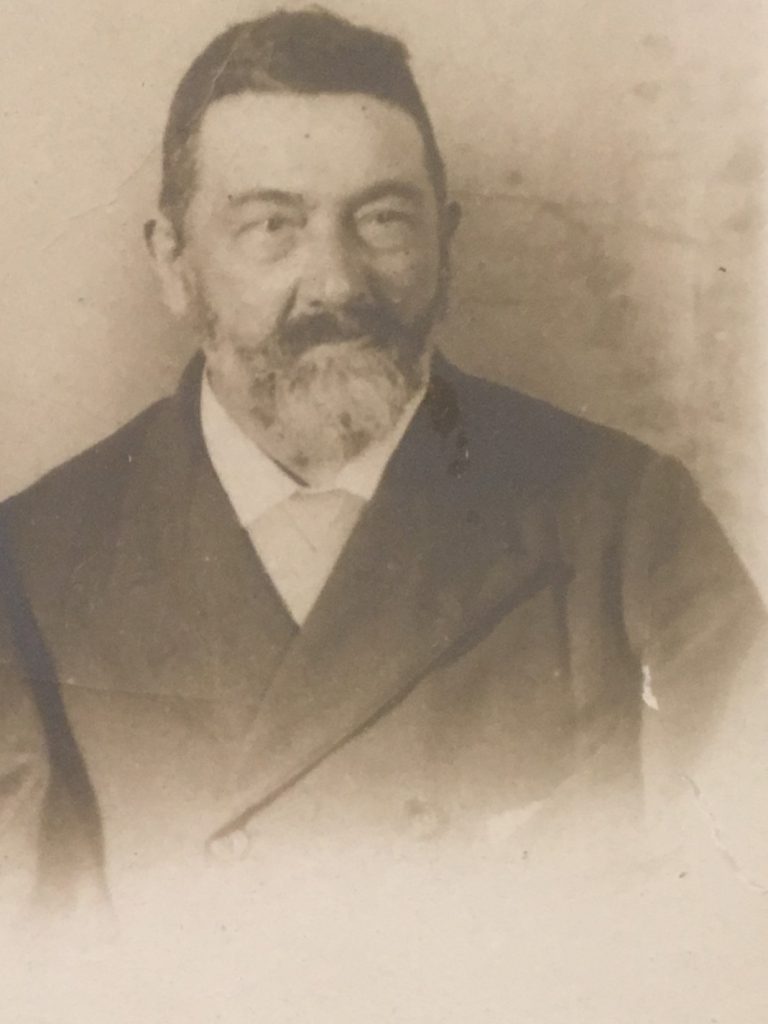

Sarasohn was born in 1835 in Paiser, Suwalki County in North-Eastern Europe. His brother in law, the typesetter and editor Mordechay Yahlomstein, escaped to America in 1861, and on 1865 he wrote back to Sarasohn, recommending him to immigrate to America and to found a printing business. Sarasohn settled in New-York in the early 1870s and opened a small printing house. The business grew successful, and the Sarasohn family would later become a prominent force in the Yiddish and Hebrew press in America.

The defendants in the trial, Phillip Krantz and Bernard Feigenbaum, were also Jews from an East-European origin. They came to America in the early 1890s with a solid socialist ideology. After arriving to New York they were involved in writing and editing the socialist weekly “Arbeter Tsaytung”, and later the socialist daily “Dos Abendblatt”, both of which funded by the Socialist Labor Party.

The articles against Sarasohn were originally published in Yiddish; the plaintiff provided a transcript and an English translation to the court. Soon enough the trial shifted from Sarasohn‟s misdeeds to the political affiliation of the defendants. In an article which was published in “Dos Abendblatt” during the trial under the title “Sarasohn informs the court on us as anarchists”, the paper claimed: “Sarasohn writes in his prosecution that we are heretic socialists, „anarchists‟, „demons‟, hoping thus to convince the American jury”. According to the journalist, Sarasohn aimed to put “socialism on trial.”

On his final address to the jury, Sarasohn‟s lawyer – his son Abraham – accused the defendants of being “socialists, anarchists, nihilists […] He told the jury that we are coming from a country (Russia) when every written line must be signed by a policeman, and because of that when we came to this free land – where there is freedom of the press, we misuse this freedom”. The verdict of the trial, given on March 1901, was in favor of Sarasohn; the jury accepted his claim and decided that the “Workingmen‟s Public Association” will pay him 3,500 dollars plus trial expenses.

The fact that Sarasohn was accusing the socialist journalists of being Russian is counterintuitive: after all, he came from a not so far region three decades earlier; he surely didn‟t think any of his newspapers were misusing the very same freedom of the press. However, by using this argument, Sarasohn was able to differentiate between himself, the “good” immigrant, and the socialists, the “bad” immigrants – a very useful differentiation in Fin-de-Siècle America.

This legal case can serve as a key for understanding the ideological and political trends of Jewish immigrants from Eastern-Europe in the first two decades of mass migration. It can also shed light on two major types of economic immigration and Americanization. These types represent different aspects of American capitalism in the 19th century: the worker(s) and the entrepreneur(s).

Sarasohn was different from his opponents in the type of the project each of them ran: “Dos Abendblatt” was an ideological and political project, rather than a profit-oriented business. Sarasohn on the other hand had a family business, not very different from other immigrant entrepreneurs in the late 19th century: it was a small scale project, ran and operated from his home at 175 East Broadway during the first years; his children were his typesetters and later became his business partners; and he didn‟t have any local background both financially and administratively. Put it this way – Sarasohn was an immigrant and an entrepreneur.

Sarasohn’s enterprise – a weekly and later a daily newspaper in Yiddish – was indeed an early form of American Jewish entrepreneurship. He had to count on family labor, communal support and home-based production. But Sarasohn‟s sweatshop was different: his product was a “Jewish” product. Unlike a pair of pants, a tie or a box of cigars – it couldn‟t have been produced and couldn‟t have been bought by non-Jews. Sarasohn needed typesetters who could read the Hebrew Alphabet, and he counted on Yiddish readers to buy his newspapers. The type of the project can also explain why Sarasohn was so worried about his reputation in the Yiddish speaking world: it was his clientele.

The 1890s New York Yiddish press represented vividly the Yiddish worlds of the city, and the main ideological debates were represented in its papers both as a subject and as an object. As the Sarasohn case shows us, understanding the role of the Yiddish press in the Jewish community of the East Side is crucial for portraying the historical and political context of the era.

Yael Levi was a Fordham-NYPL Research Fellow in Jewish Studies in the spring of 2019. Below is the lecture she delivered at Fordham University in April 2018.