Curated by Wes Alcenat, Corinne Gibson FCRH’24, and Magda Teter

Walsh Family Library, O’Hare Special Collections, September 15-November 1, 2024

Debates over who belongs and who should be eligible for citizenship go back to the late eighteenth century when new political systems began to emerge after the American and French Revolutions. These debates did not just address the question of who belongs but also, since the idea of citizenship was so new, what it means. In Europe, the question was framed around race, religion, and political rights; in the United States–where slavery was flourishing, around race, since religion became a constitutionally protected category. Past legal and social status influenced these debates and outcomes.

This exhibition explores the ways that exclusion affects minority groups in Western-dominant societies. It explores the ways in which Jews were excluded from European Christian-dominated society based on Christian notions of Jewish inferiority and the way Black people were excluded and marginalized in the United States and Europe based on race and association with slavery. We contemplate the idea of citizenship and belonging not only from the perspective of inclusion but also from the perspective of legal and social exclusion. We examine mechanisms of marginalization and exclusion: marking people and spaces, use of language, law, and also violence. We also examine the way these marginalized groups navigated exclusion, highlighting their coping mechanisms, resilience, and resistance to oppression and their unabashed demands of full equality and inclusion. We confront here this critical chapter in the history of the U.S., Europe, and the Western Hemisphere to better reflect on its enduring impact on the ongoing struggle for justice in “Citizenship, Inclusion, and The Right to Belong.”

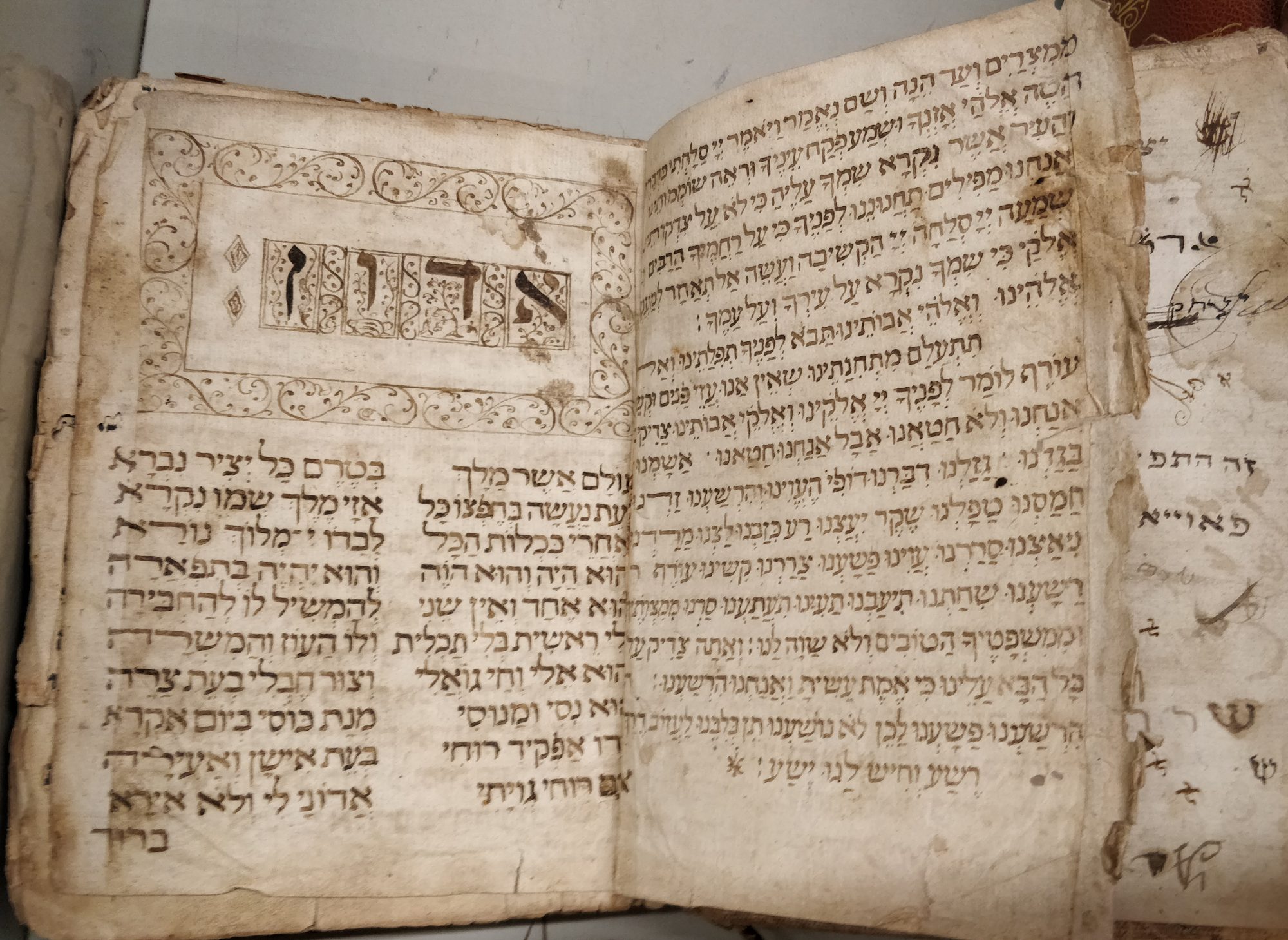

In the premodern period–before the end of the eighteenth century–under both Christianity and Islam, Jews were marked by “badges of inferiority.” In Christendom, they were considered doomed to “perpetual servitude” in theology and law and subjected to legal restrictions. For example, they were prohibited from hiring Christians, holding public office, or living in respectable sections of towns. In some places, Jews were required to wear badges or yellow hats, marking them as Jews. In Italy, they were forced into ghettos. Under Islam, they–along with other non-Muslims–were considered dhimmi, a status that granted protection but also restrictions meant to remind them about their religious, social, and legal inferiority. Shown in the exhibit are decrees related to the establishment of the ghetto in Ferrara in 1624. They regulate rents, create rules for businesses, and Jewish-Christian interaction.

This document concerns ghetto boundaries, real estate, rents for houses and stores, sumptuary laws, including prohibition to wear luxurious dress and display wealth, Jewish-Christian interaction, and lending rates in Ferrara.

The European colonial expansion in the fifteenth century not only changed global geography and power structures but also led to major population shifts–with millions of Africans involuntarily transported to the Americas. The mass enslavement of Africans led to the development of the Western idea of “race” to justify the brutal enslavement and the European colonial expansion. Blackness came to mean inferiority. But while Jews had to be required to be marked, the skin color of Black people marked them and linked to the legacy slavery. This legacy is still felt today.

The exhibit shows a manumission document from 1798 from Allegany county in Maryland, one issue from 1860 of William Garrison’s abolitionist paper The Liberator, which was published between 1831 and 1865, and a 1863 document from Cuba outlining the obligations concerning hiring “emancipated blacks” [negros emancipados].

Slave manumission, 1798, Allegany County, Maryland (manuscript). This slave manumission manuscript from 1798 is a legal document freeing an enslaved man referred to as “Negro Joe” from the ownership of slave owner, John Lynn.

The idea of citizenship implied not only equality before the law but also political power. In Europe the inclusion of Jews in the polity was vigorously debated in the eighteenth century. During the French Revolution, the idea of “all men were born equal” was challenged when it came to the inclusion of Jews and people of color and their status in the French colonies. The two topics were hotly debated. In the end, Jews were reluctantly admitted to citizenship, first the Sephardic Jews of Bordeaux and other communities, in 1790, and then in 1791, over two years after the declaration of the rights of man and citizen, also Ashkenazi Jew in Lorraine and Alsace. The question of the colonies, however, remained outstanding. Ultimately, the rebellion in San Domingue led to the creation of a new state, Haiti, the only one in the Western Hemisphere that banned slavery. Items displayed here show the centrality of these debates about Jews and Black people—free and enslaved—in Europe, both before and during the French Revolution. Shown in the exhibit are Dissertation sur cette question: Est-il des moyends de rendre le Juifs plus heureux et plus utiles en France? (Metz: 1788), which considers the question of how to make Jews “happier and more useful in France.” Numero 299 Journal de Paris, Lundi 26 Octobre 1789, a gazette with an announcement from the Assemble Nationale about the deputation of “Citizens of Color from our Colonies to the National Assembly,” illustrating the issue of the status of the colonies in the citizenship debates during the French Revolution. Deputés de Juifs de Bordeaux, Adresse a L’Assemble National. December 31, 1789, an address by representatives of Jews from Bordeaux, December 31, 1789, demanding full rights as French citizens, which was granted to them in January 1790; Proclamation du Roi sur un Décret de l’Assemblée Nationale, concernant les Juifs. April 18, 1790, extending protection of Jews in Alsace but it stopping short of admitting these Jews to French citizenship. Jews of Alsace and Lorraine would wait until September 1791 to be grated rights of “full” citizens. Lettres-Patentes du Roi, sur un Decret de l’Assemblee Nationale portant que les … qui reglent les condition necessaires pour etre Citoyen actif, 23 Avril 1790, a proclamation by King Louis XVI affirming that “the previous Decrees” passed by the National Assembly on April 10th, 1790, regulating “the conditions necessary to be an active Citizen will be executed in all circumstances without any exceptions whatsoever.”

The exhibit then explores not only the limitations on rights after the acquisition of legal status as citizens, such as Jim Crow segregation, exclusionary violence, proposals of deportations and other means of removal of Jews and Black people from polities, but also ways in which Jews and Black Americans asserted their belonging and struggled for their rights and dignity.

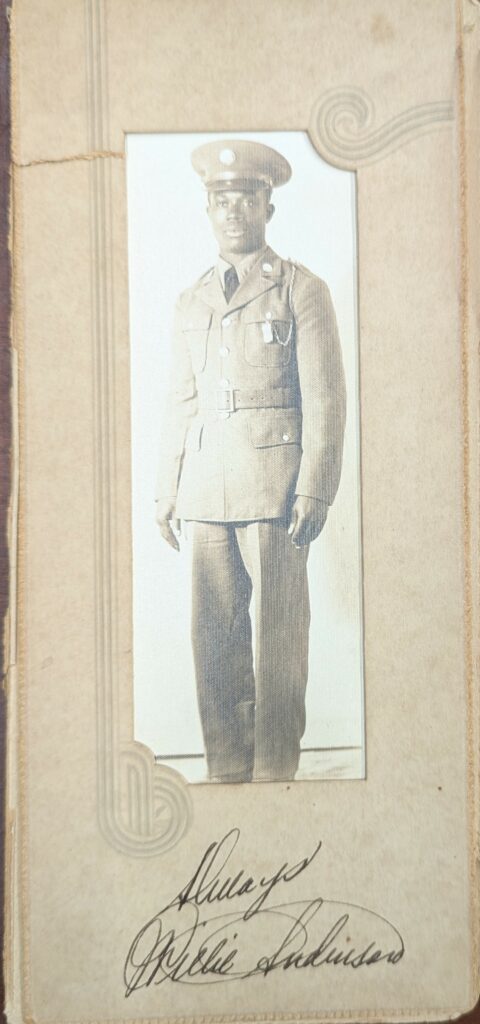

Both Black Americans and Jews were burdened by having to prove their patriotism, affirm their readiness to serve the country and die for it, even when the country’s majority put a doubting asterisk or legal restrictions on their place. Military service was one way to demonstrate patriotism and commitment to the country. But military service was not always open to Jews and Black Americans. Jewish loyalty was questioned, opponents argued that Jews would not fight on the Sabbath, nor would they share food with non-Jewish soldiers. In France, a French army officer, Alfred Dreyfus, who was falsely accused of spying against France and publicly humiliated in a ceremony stripping his army rank. Though he was later exonerated, the Dreyfus Affair incited a virulent antisemitic movement in France, drumming up claims of Jewish disloyalty. Black Americans, while not excluded from military service, were segregated and destined for low-rank positions. During World War I, for example, the War Department drafted Black soldiers but with the intention to use their labor, not train them–with guns–for the battlefield. For both Jews and Black Americans, military service, then, was a way to demonstrate that they were honorable and loyal citizens, and that they rightfully deserved to belong.

A turn-of-the-century photo of a Black American soldier signed, Always, Willie Anderson (?) and Prayer Book for the Solemn Days for Jewish members of the Australian Fighting Forces (Sydney: Hogbin Coker, 1943). A World War II-era prayerbook for Jewish soldiers in the Australian armed forces.

The demand of “equality before the law, equality in security of the person, equality in human dignity” were not just lofty ideas. They also translated to expectations and hopes in daily life, on which they had a tangible impact. This case shows two family albums, one of a Jewish family–the Schwalb-Rosenhain family–in the Bronx, and the other of a Black family—the extensive Lindell Family–from St. Louis. Each album shows “private photography,” with loved ones, private moments, and memories. But part of those private memories and moments were also statements on political belonging: service in the military and political engagement. In short, a life with dignity, equality, and security that any citizen hoped for but some were thwarted to fully enjoy. If citizenship in the United States was from the earliest years of the country defined along racial lines–did these families aspire to “whiteness”? Or did they assert their dignity and rightful place as citizens in American society reclaiming what citizenship means? These albums capture the private memories these families wanted to be preserved. An outside viewer misses the stories these photographs capture.

The album features the family of Morris Schwalb, a NYS judge, and his wife Evelyn Rosenhain, daughter of Max and Henrietta Rosenhain. It includes the pictures of their children and parents, and even grandparents.

Lindell Family Album, St. Louis, MO (bottom)

The album includes photographs going back to the early twentieth century, clippings from newspapers, and memorabilia. It highlights what the family wanted to remember. The pain and oppression experienced by Black families in the United States may not be visible to the naked eye of the viewer but each photograph captures their resilience.

The exhibition would not have been possible without the generosity of Eugene Shvidler, whose gift to Fordham’s Jewish Studies program helped start Fordham’s Judaica collection. Over the years, Fordham’s trustees Henry S. Miller, Donna Smolens, Eileen Sudler, Dario Werthein, as well as members of the CJS advisory board, many anonymous donors and friends of the Center helped the collection grow and allowed us to create an internship program that supports student research and exhibit curation at the Walsh Library. We are grateful to the Director of Fordham Libraries, Linda Loschiavo, for her support and to Gabriela DiMeglio and Vivian Shen of the Special Collections and Archives for their tireless support of students’ work and their help with setting up the exhibits.