by Boaz Huss (Ben Gurion University, Israel and a past Fordham-NYPL Fellow in Jewish Studies)

In 1888, Isaac Myer published, in Philadelphia, a book entitled Qabbalah – The Philosophical Writings of Solomon Ben Yehuda Ibn Gabirol. It was the first comprehensive book on Kabbalah printed in the United States, and the most learned and up to date book on Kabbalah in English at the time.

Isaac Myer was born in Philadelphia in 1836. His ancestors, who immigrated to America in the 17th century from England and from Holland, were Puritans and Dutch reform. His father, Isaac Myer senior, was a wealthy businessperson. Isaac Jr. graduated from the law department of the University of Pennsylvania in 1857. He practiced law in Philadelphia and New-York and was United States Commissioner of western Pennsylvania. He was a private scholar, a Freemason, and a member of several scholarly and antiquarian associations.

Myer published several books, which can give us an impression of the wide range of his interests. They include Presidential Power over Personal Liberty (1862); The Waterloo Medal (1885); The Qabalah (1888); Scarabs (1894); and his last book The Oldest Books in the World (1900). He also published several articles, which include articles on Hermes Trismegistus and on Hindu Symbolism published in The Path, an article on “On Dreams by Synesius,” published in The Platonist, and an article entitled “Qabbalah, Quotations from the Zohar and other writings, treating of the Qabbalistic or Divine Philosophy,” published in The Oriental Review.

Myer’s was especially interested in Kabbalah. He presented his unique ideas about Kabbalah in his major book, Qabbalah, as well as in some of his other writings. His views on the history and significance of Kabbalah are based on comparative and philological-historical research. However, his interest in Kabbalah and comparative religion was not purely historical. It had a theological, spiritual aim. Myer believed that the study of Kabbalah and its ancient origins will revive Christian mysticism, and will enable the formation of a new theology, that will reunite all divided religions.

Myer died in 1902 and was buried in the family lot at Laurel Hill, Philadelphia. Myer bequeathed his rich library, and many of his own manuscripts, to the Lenox library, which became part of the New York Public Library.

Isaac Myers` papers are found today at the Manuscripts and Archives Division of the NYPL. They contain 11 boxes of Myer’s manuscripts. On November 2017, I spent a few weeks studying this vast collection, with the support of the NYPL and Fordham University grant. I have recently presented the results of my research, at the opening of the conference “Kabbalah in America,” held at Rice University.

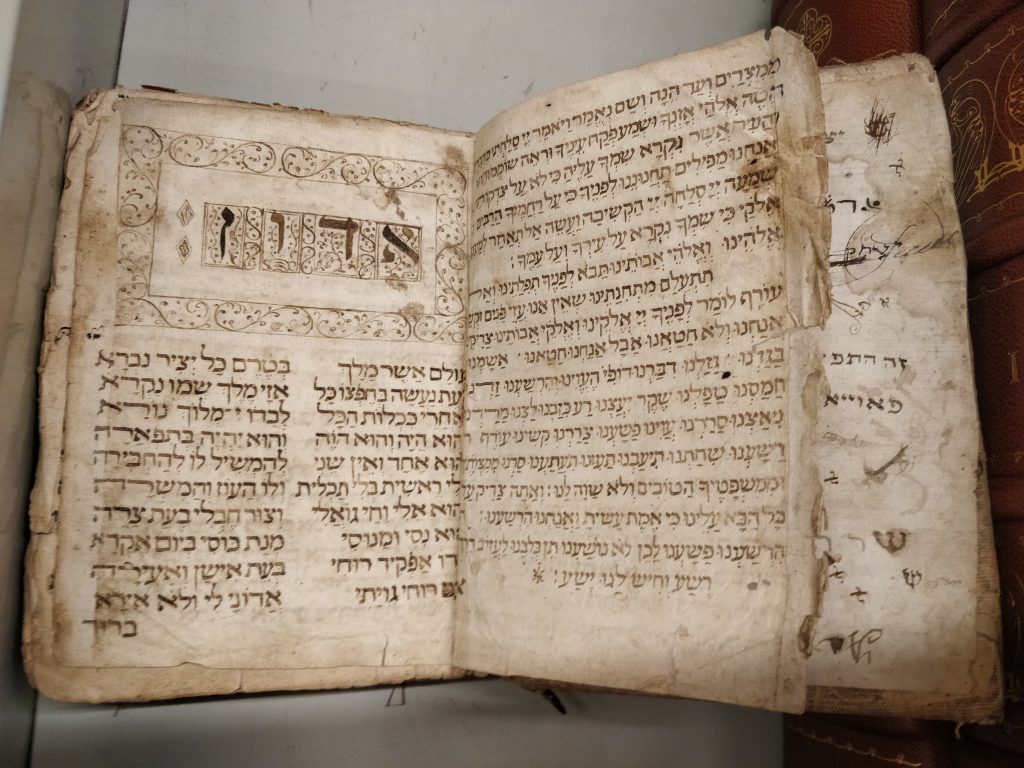

Myer’s Collection consists of manuscripts of his published and unpublished works, as well as many translations, transcriptions, commentaries, bibliographies, and indexes related to his research of Kabbalah and other ancient religions, as well as to federalism and constitutional history. Myers’ papers also include several letters, that provide valuable information about Myers’ affiliation and networks.

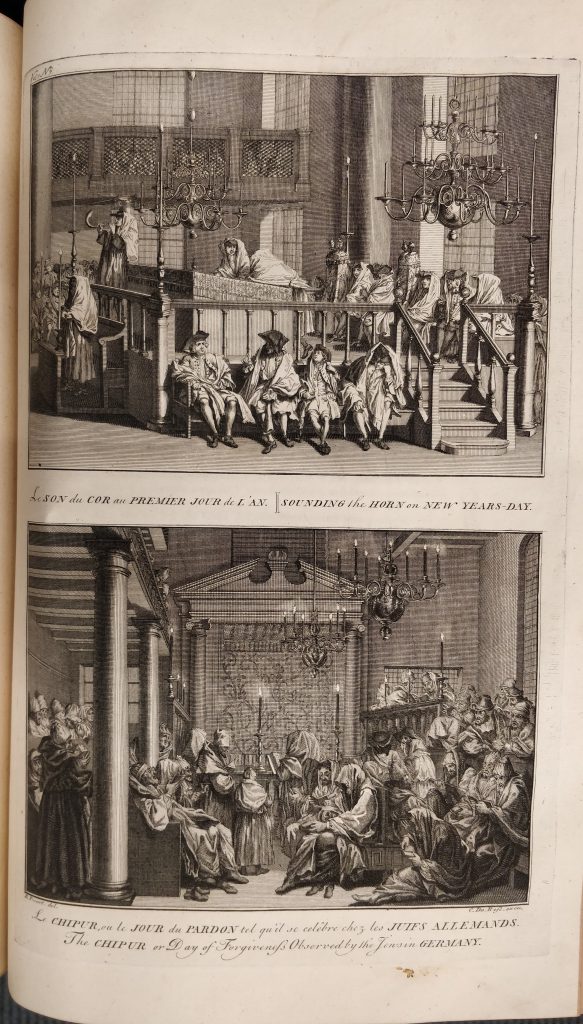

Myer translated to English dozens of books and articles, mostly on Kabbalah, from Latin, French, German, Hebrew, and Aramaic. They include western esoteric and occult works, such as Franz Molitor’s Philosophy of History and works of Eliphas Levi; 19th-century German Jewish scholarship of Kabbalah, including translations from Heinrich Graetz, History of the Jews and Adolph Jellinek’s Selection of Jewish Mysticism and books on Kabbalah in Hebrew, such as Moshe Kunitz`, Ben-Yochai and Abraham Baer Gotlober’s, History of Kabbalah and Hasidut. Myer also translated primary Kabbalistic texts, from Hebrew and Aramaic, such as Ibn Gabai’s Derekh Emuna, and many passages from the Zohar. The archive reveals the Myer was the most knowledgeable person about Kabbalah in the United States in his period.

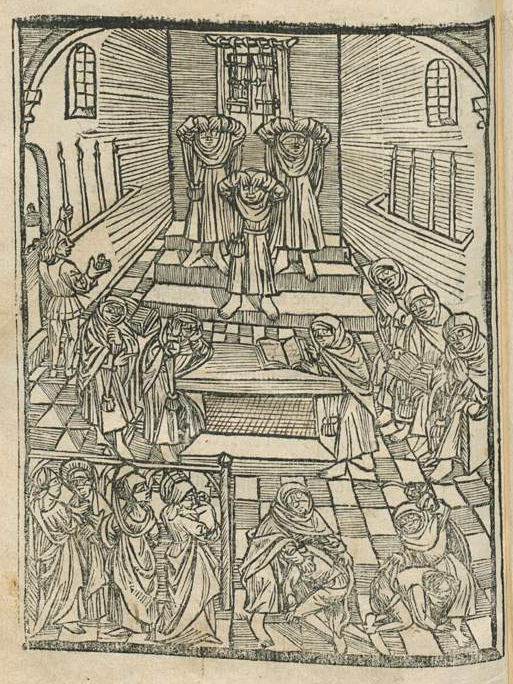

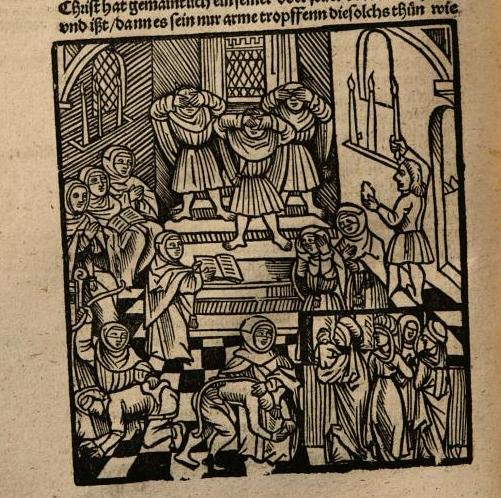

Apart from the manuscripts of his published work, Myer’s collection includes also drafts of several unpublished articles, as well as a draft of a book about Johannes Kelpius (1667-1708), the 17th-century German pietist who immigrated with his followers to Pennsylvania in anticipation of the end of the world. The collection also includes Myer’s eulogy to his friend and patron, Eli K. Price (1797-1884), a lawyer and independent scholar, who the president of the Philadelphia Numismatic and antiquarian society.

Most interesting are the letters found in Myer’s archive, that shed some light on Myer’s networks and the context of his unique interest and perception on Kabbalah. These include correspondence with Thomas Moore Johnson (1851-1919), from Osceola, Missouri, the editor of the journal The Platonist, who was (similar to Myer), an eminent attorney, independent scholar, and an occultist. Another interesting letter found in the archives is a letter from Merwin-Marie Snell (1863-1921) dated May 30, 1894. Snell, one of the first scholars of comparative religion, came from a prominent New England protestant family but converted to Catholicism. He published several books, and he is known as one of the organizers of the famous World Parliament of Religions in 1893. He was interested in esotericism and was the founder of one of the most learned, and mysterious occult movement, The Universal Brotherhood.

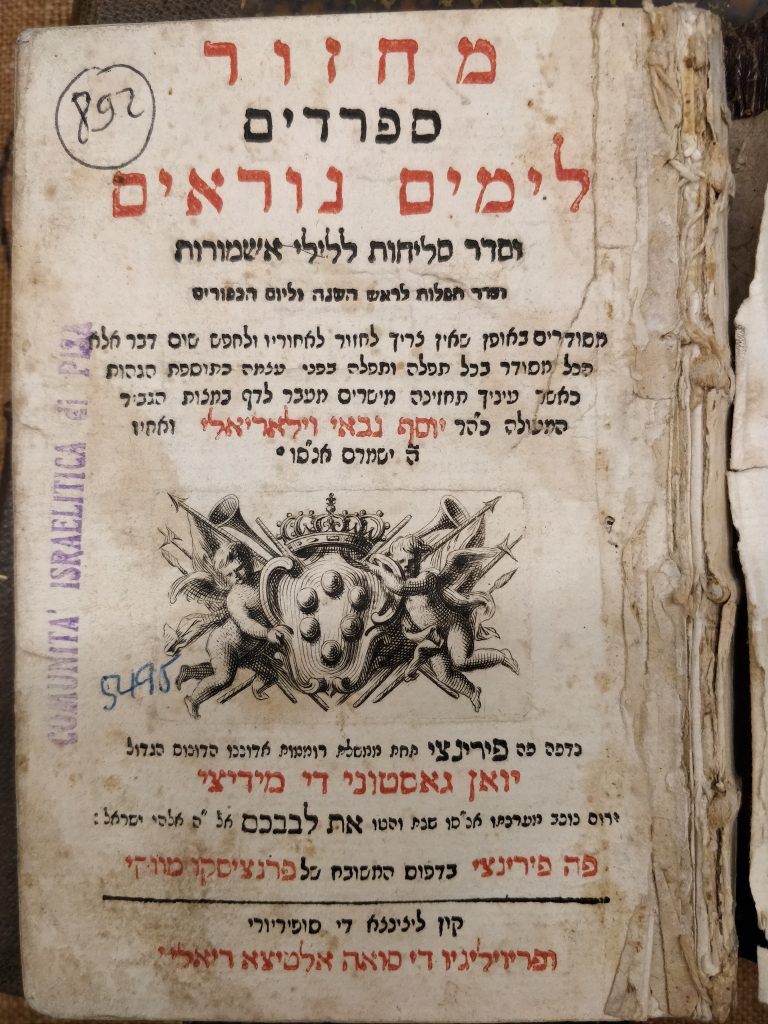

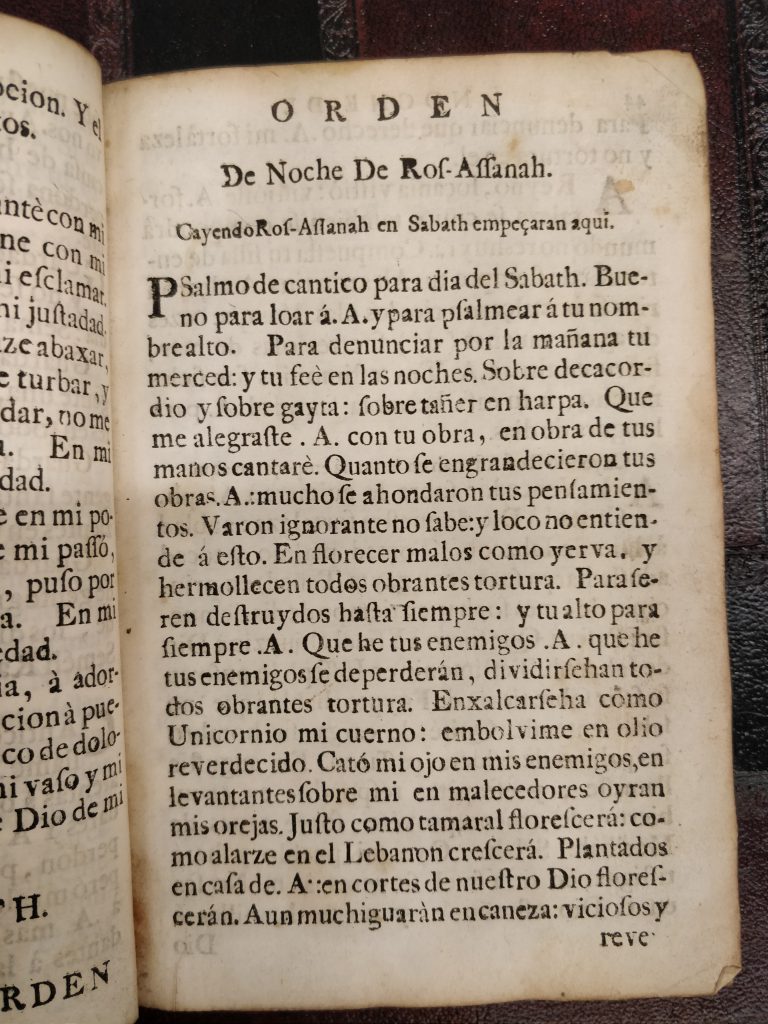

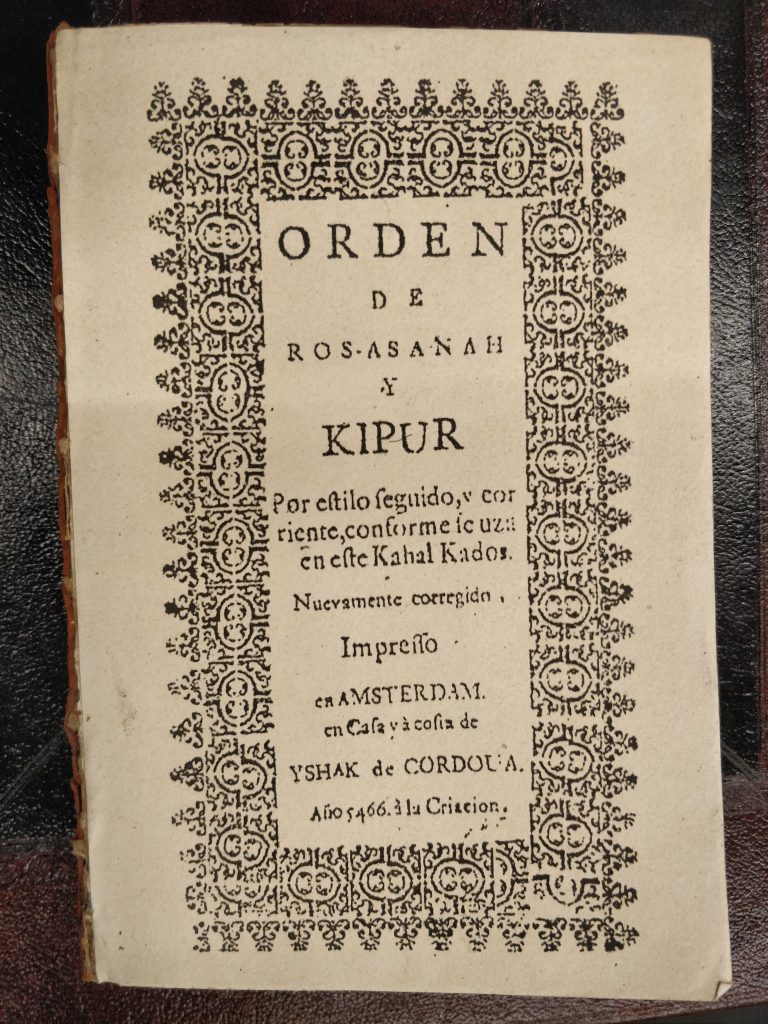

Myer correspondent also with several Jewish scholars and Rabbis, who helped him in his research of Kabbalah. The archives include a letter which was sent to Myer by Sabato Morais (1823-1897). Morias, originally from Livorno, Italy, was for many years the head of the Orthodox Synagogue Mikveh Yisrael in Philadelphia. He was one of the most important American Jewish scholars and leaders of the late 19th century and was involved in International, American and Jewish public and political issues. In 1886, he founded, as was the first president of the original Jewish Theological Seminary in New York.

Another Jewish scholar who corresponded with Myer was Henri (Zvi Hirsch) Gersoni (1844-1897). Gersoni who was born in Vilnius, was a Journalist, author, and rabbi, and published extensively on various topics in Hebrew, Yiddish, and English. In Myer’s archive, I found a package that contained Gersoni’s translations of Hebrew and Aramaic texts from Adolphe Jellinek’s Beitrage zur Kabbalah. It also included correspondence between Myer and Gersoni, from 1885, regarding translations of different Kabbalistic texts. Another person Myer corresponded with was Chajim David Lippe, a Jewish publisher, and bibliographer from Wien. The study of Myer’s papers at the NYPL sheds light on Myers’ wide scholarly interests and on his unique knowledge and perception of Kabbalah. The archive reveals Myers’s scholarly and esoteric affiliations and networks, which were quite wide and interesting. The occult and scholarly networks, to which Myer belonged, helped to shape other modern forms and perceptions of Kabbalah, which developed and became popular in America in a later period. Although Myer`s erudition and interests in Kabbalah were unique in his time, many of the characteristics of his modern American Kabbalah will also characterize later forms of Kabbalah in America.